Adrianne Beer

Short Fiction

Seagulls was named a finalist in the 2025 Clarissa Dalloway Prize for Short Prose, judged by Diane Josefowicz

I got to Chicago in March. The city was still painted gray with salt, but on a clear day at 3:00 PM, I was told spring was coming soon. I rented a lopsided, studio apartment next to the El. When I got there, it was so loud I worried I might kill myself. The time between trains was just long enough to think they had stopped for good. After a few hours I never noticed it again. My father picked me up a mattress in Rogers Park for ninety dollars while my mother unpacked all the kitchenware she could part with. A ceramic tea kettle and three crockpots. When they left to go back to Ohio, they were awkward and didn’t know how to say goodbye. My mother mentioned Easter being soon as she quickly hugged me. My father told me he put mace on my apartment keys and fifty dollars on the counter, then he squeezed my fingers with his smooth hands. That night, I listened to the city. The buzz of the apartment building doors, the sorts of sirens, and cars on the street like rushing water. I was so loud growing up; the city noise drowned out that shame.

In the week before I started my job, I spent most of the time looking out the window. I kept a running list of places I wanted to go, but each time I got my keys to leave I thought of the reasons I shouldn’t. My bathroom faucet dripped; it would overflow. I expected a package; if I wasn’t home, Chicago would swallow it back, lost for months. The few times I left my apartment I wanted to tell everyone that I wasn’t from there. I wanted to excuse myself for the way I crossed the street and my nervousness in crowded coffee shops. I didn’t know where to stand so I investigated the milk too long. I wondered if people could tell on public transit. I moved around for the most stable position, scared to remove my hand from the bar. The third time I rode the train, it was rush hour. It was so crowded I couldn’t find something to hold on to. A man my age and height noticed my stress. He nodded to his shoulder. He felt sturdier than I expected. I bet he was a father. After, I choose my commute based on what train would be least crowded.

I was a “Practice Representative” at a chiropractor’s office. My supervisor, the chiropractor, liked us calling him Dr. Neilson. I called him Justin. We spoke two times before he hired me. First, over the phone, beneath a Louisville overpass, while I waited for the Greyhound to take me somewhere else. Our connection kept getting cut off, but he didn’t notice. He listed his degrees, described the position six times, reading directly from the Indeed post, and then asked, “So, do you think you can do it?”

I responded, “Yes, I think I would be a great fit.”

There were two other employees, a front desk attendant and Justin’s assistant. We were all women in our twenties. My title was misleading; it was a door-to-door sales position. I walked to businesses around the neighborhood and asked if the staff would be interested in getting a free lunch. With a free lunch, they’d receive an informational session about our practice. This is how we got new clients, which we didn’t have many of. It was because of the millennials and their unwillingness to buy products like napkins.

During my first shift, Justin drove me around Lincoln Park to show me the area I would walk. He drove a black Dodge Charger aggressively and wore a buttoned shirt with the top two buttons undone, revealing strawberry chest hair. He was girl dad who lived in Schaumburg with his wife. He got his two daughters a swing set for Christmas, but the ground was too hard to install it.

Most of my job was spent outside and I worked in the makeshift back room when I needed to send emails. I could see Justin’s clients through a space between two pony walls that made up his “repair” room. I could hear him adjusting his clients on the treatment table. The pops reminded me of water drops in oil and made me uneasy. Every day I took two cigarette breaks. I only smoked during the second. The alley smelled of laundry detergent and Mountain Dew. A guy from the pizza shop waved when pulling in and out for deliveries. I daydreamed about the alliance we could create, Workers of Shitty Lincoln Park Mini Strip Malls. We would ask the Potbelly’s workers too, and in the listserv we’d share all our employee discount codes.

When I felt particularly lonely and missed Ohio, I took a bus to the suburbs. Just the sight of wider streets made me feel at ease. I would spend an entire Saturday at the mall, walking around while on the phone with my mother. Every time we talked she told me where she got the dress pants I liked. The same Nelly Furtado song played in the Gap, Brookstone, and Sunglass Hut. It reminded me of the time I was date raped in college. I ate twelve dollars worth of Auntie Anne’s pretzels in the food court while I watched mothers rub stuff off their children’s clothes and faces. On the bus ride back, I picked at the filth beneath my fingernails and wondered which Midwest I preferred.

I made one friend in the first three months of living there. He worked at the convenience store down the street. After his shifts he brought over snacks and weed. The second time we smoked, I took too big of a hit and wigged out. He told me eating sweet things could dim the anxiety. Zebra Cakes were our favorites. I liked him most when he did not shave and when he left in the morning before I woke up. I could have fallen in love with him if the way he ate didn’t bother me so much. Each bite was as if he was trying to decipher what it was, timidly and with too much attention.

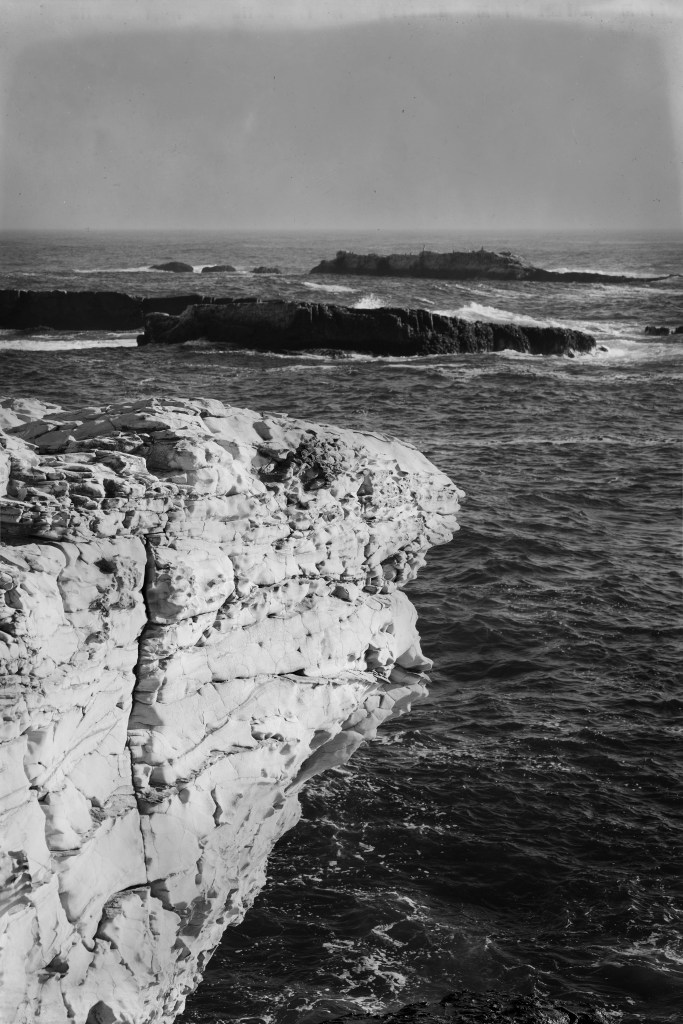

We walked to the lake together once because he made fun of me for not having been yet. I was surprised by how big it was up close and the prevalence of concrete. If I didn’t know the Great Lakes, I would have called it an ocean. We ate Bahn mi sandwiches while I wondered how much of where seagulls go was just the wind.

“How’s this compared to Ohio?” He asked, nodding to the waves beating against the city scape.

“We have lakes,” I scoffed. Beneath my defense, I knew ours were not in the same bracket.

“My cousin is going to Dollywood next month,” he said. He thought Ohio was the South.

On weekday afternoons, I walked out of the train station to the smell of deep-fried sugar batter from the churro window. It reminded me of county fairs and the funnel cakes that left me white and sticky. When the temperature dropped below 40 degrees, the door to my building didn’t close all the way. Once I was in my apartment, I opened every closet to make sure I was alone, then stripped off my layers. Most nights I took a bath to cure the Chicago cold in my bones. I could hear the downstairs neighbors clearly from inside my tub, as if they lived in the drain. The girl talked ceaselessly on the phone, mostly about how every time her boyfriend ran the dishwasher nothing got clean. It felt like home; not in the way that I belonged there but in the way I mistook the sound and smell for my childhood bathroom.

On Fridays, only Justin and I worked. He usually had one client. She was slightly pregnant and came in every week. I measured her stomach in my mind each visit. That day, I bet the baby was the size of a cream cheese ball. The kind my mother used to get at the deli. The woman complained about lower back pain and Justin was more comforting than I thought he could be. I responded to six emails and stared off into the room, wondering if I could see the cream cheese ball grow. When Justin got to the women’s feet, I didn’t turn away quickly enough and he caught my gaze. He winked. I pretended to work for the next twenty minutes.

Once the pregnant women left, I began to pack up my things. When I turned to leave, Justin was standing in the hallway. He was looking directly at me, and his hand stroked his bare penis. He pulled down his pants slightly lower. I could see his balls move back and forth in rhythm with his hand. I looked up to his face. His eyes were halfway closed, peering at me while he gnawed at the side of his bottom lip. He reminded me of a small child who was trying to complete a task his fingers were too clumsy for. I stood there until he came. His ejaculation poured onto the thigh of his pants. I grabbed my bag and left out the back.

On the train toward my apartment, the women in the seat next to me opened a tightly sealed, half-drunk, orange Fanta. I could see the bubbles popping out and spitting onto my coat sleeve. It made me nauseated, the sweetness.

Adrianne Beer received her BFA in creative writing from Bowling Green State University and went to library school at the University of Arizona. She is from Yellow Springs, Ohio. Her writing can be found in Moon City Review, Chicago Reader, Southwestern American Literature, Roanoke Review, and elsewhere.

Photo Credit: Arina Anoschenko