Andrew V. Lorenzen

Short Fiction

The eco-terrorist is zipping down the highway in a 1996 Ford Aerostar. He keeps laying on the brake, even though there’s hardly any traffic going east in the mid-afternoon. You’d think that’s out of caution. The man does have a bomb, after all, and even suicide bombers get nervous about popping off before the requisite moment. But the real reason the gaunt, jaundice-eyed figure is driving so daintily is that he’s simultaneously trying to dip Oreos into his Pepsi, and he stupidly purchased a can, rather than a fountain soda. The hole’s just not large enough to accommodate the cookie. Oreo after Oreo disintegrates in his clammy hands as he tries to shove them into the soda. He curses himself for making this silly mistake. He’d been attempting to recreate a fond memory from his youth, in which his first and last girlfriend—11th grade, bubblegum lip balm, an affinity for the musical stylings of Karen Carpenter—taught him the odd culinary pairing. (He is sentimental, mass murder notwithstanding.) He gives up as he pulls the car to the exit, down the busier Main Street, and parks it outside the convention center, unwittingly next to a fire hydrant. The van’s engine idles, a trickle of smoke dribbling from the tailpipe. The eco-terrorist takes a deep breath and arms the weapon. The plan is to blow up the oil conference. He will die a hero, in his own mind. But the oil conference is next Saturday. It’s a philosophy conference today.

The bomb is set to go off in four minutes and twelve seconds. The average person reads at a rate of two hundred and thirty-eight words per minute. That leaves us almost exactly one thousand words until everything blows up. We best choose our words carefully.

In the convention hall, a gaggle of graduate students and professors nod along to the wild gesticulations of the man onstage. He’s middle-aged, his stomach protruding from his tight black turtleneck. He paces around a wooden stool, upon which is a tall glass of lukewarm milk.

He’s demonstrating a jargon-free method of explaining object-oriented ontology. He’s asking—rhetorically—why is there any more value in a human life than in this glass of milk?

A white-haired, bearded man in the audience—apparently not familiar with rhetorical questions—yells, “Because we decide there’s not. We get to decide what has life, what has meaning.”

The turtlenecked gentleman casts him an Ivy League glare before asking, “But who are we to decide? What gives us the right?”

In the bathroom outside of the hall, two graduate students are having sex. The bathroom is out-of-order. The lights are out, but the sun is streaming in through the window, casting their shadows against the wall. Their dark outlines heave into one another, bending and contorting into one shared image. They haven’t known each other for long, though they’ll marry if they live through the bombing. They’re only reluctantly at this conference to impress a shared professor. The conversation that preceded their intercourse was as follows:

“I’d like to think I’m a good man.”

“There’s no such thing. There are no good and evil people. Just people.”

“Then why do we do good things?”

“Same reasons we do anything else. Sex and power.”

“But then everyone would be evil. You’re better off being evil if that’s all you want.”

“No, it’s a tactic like anything else. People like the good. People fuck the good. People vote for the good. Sometimes, anyway. It’s choosing one half of a circle. It all ends in the same point.”

“Circles don’t end in a point. They don’t end at all. That’s, like, the whole thing with circles.”

“You know what I mean. The point is people suck.”

“You’re a cheery gal, you know that?”

“Hey at least I believe in free will.”

“Well, let’s use our respective free wills to talk about something else.”

“Should we fuck?”

And they did. If they live, they’ll have an ugly divorce (infidelity; credit card debt). And when they do die in old age, of natural causes, they’ll each be alone, longing for the other, longing to see their shadows collide just once more.

There’s a married couple just outside that bathroom door. They’re pacing through the convention center. The man in the baseball cap needs breaks. He was an insurance actuary until being struck by lightning, at which point his faculty for numbers and continence diminished. He’s since become obsessed with the philosophy of Martin Heidegger, to the point of hanging a borderline life-sized portrait of the German in his living room.

This rather intense new obsession has led the man’s husband—the gentleman in the aqua marine Ralph Lauren polo holding his arm—to worry that there’s been some, well, changes to his spouse’s brain chemistry. Other things have gone haywire as well. The lightning-favored man was trying to hum the Jeopardy theme while his husband was taking ages to get ready this morning, but he was actually humming “The Girl from Ipanema,” which is “their” song, the song that played when they first met in a port bar in Mexico during a discount Caribbean cruise. He keeps thinking that he’s humming different songs, but he always hums “The Girl from Ipanema.” It makes light-blue polo guy love him even more, despite it all.

Outside, a meter maid is writing tickets. She’s wearing a pink crochet sweater adorned with two kissing flamingos, the outlines of their necks creating a heart—she has no one. She eats a Lean Cuisine Chicken Fettuccine Alfredo every night and watches The Office. But when she wears that sweater, sometimes people think a lover knitted it for her. They ask her about it, and she blushes, shyly, saying, “It’s so embarrassing” but she wears it not to hurt their feelings. She finishes writing a ticket. She looks up and sees the eco-terrorist’s van idling. That’s odd, she thinks. Who dips Oreos in Pepsi?

The turtlenecked presenter onstage is getting angsty. His heckler keeps pressing further. Turtleneck casts a glance to his infant daughter, who’s sitting in the third row with her mother and her favored stuffed animal: a one-eyed, molting Babar the Elephant.

The heckler asks, “But how do we construct value in things? By the act of perception. By connecting it to our own human experience. What is a glass of milk without our understanding that milk can nurse a child?”

Turtleneck retorts, “Things should not have value merely because of the human gaze. Things should have value. Humans are biased. We make value in only what we perceive. That’s the—” he’s cut off by the glass of milk being caught by the gesture of his right hand. It crashes onto the stage-floor, shattering into pieces and sending droplets of milk into the front row.

In the bathroom, the graduate students stop thrusting. In the lobby, the married couple stops strolling. In the parking lot, the meter maid stops writing a ticket. In this world, all stands still for this single, aching moment.

“There, you see!” the heckler says. “If we only see the aftermath, if we only see the glass and liquid on the floor, it has no meaning for us. It could be anything. We haven’t any idea that it was once a glass, that it once held milk, that the milk was destined to be drunk by someone. We need the story that caused it to be broken, man. Otherwise, we’re empty. Otherwise, we haven’t any idea that we should cry over spilled—

After attaining an MFA in Creative Writing from New York University, Andrew V. Lorenzen was named a 2024 Marshall Scholar and now is pursuing an MSc in Politics and Communication at the London School of Economics. Lorenzen’s work has previously been published in The Nation, Cleaver Magazine, The Miami Herald, and The Chronicle of Higher Education. To learn more about his writing, visit: www.andrewvincenzolorenzen.com

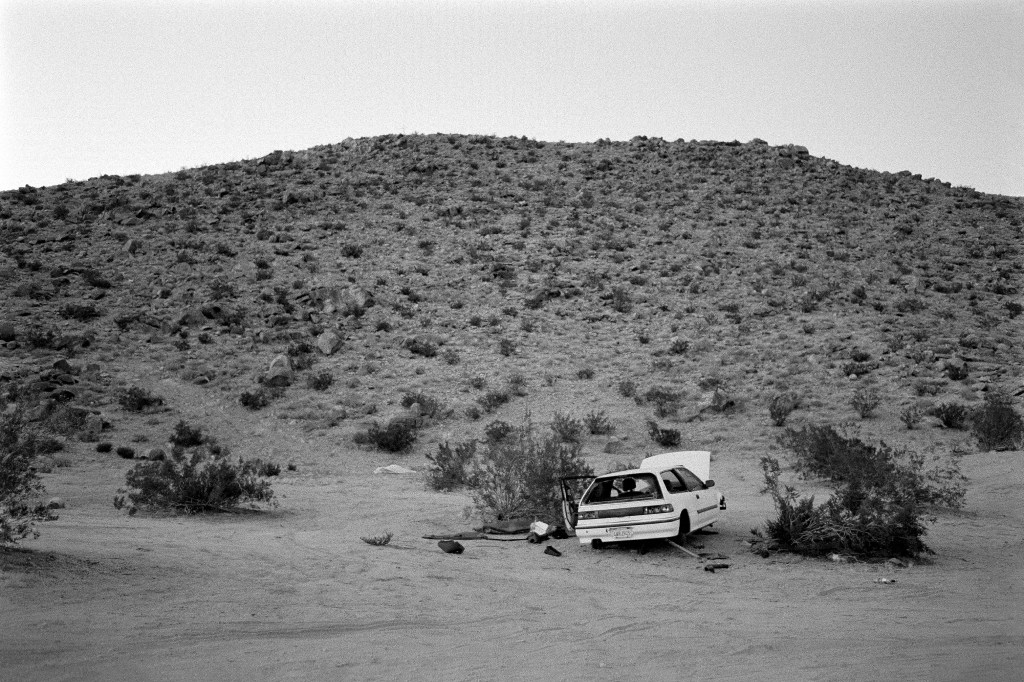

Photo Credit: Charlotte Toumanoff is a photographic artist, specializing in the intersection between stillness and kinetics through memory and documentation. Having received her BA in Cinema and Media Studies at the University of Pennsylvania and studying Creative Writing at the University of Oxford, she is fascinated by the storytelling power of images. Her work seeks to examine concepts of the ephemeral and the immortal and their collision in everyday life. Her photographs have been displayed in the Griffin Museum of Photography.