Point of View, Narrative Mode, and Feminist Existentialism in Rachel Cusk’s Arlington Park

D. W. White

Literary Criticism

And why had they come to Arlington Park at all, if not to provide their children with a garden?

Time, we learn from birth, is unconcerned with death. Or perhaps they are one, two cloaks worn by the same end. It all depends, really, on one’s point-of-view. The blackness of Goya’s walls, the warlike lamentations of pensive Macbeth, the cagey advice Teiresias lends to Odysseus’ katabasis. Time, with his sickle and his certainty, seems prepared for any eventuality. And this we know to be true, despite the comfort of denial. While eternity has no equal, however, it has at least worthy adversaries; none so intrepid or resilient as narrative. If there is one remedy to an untimely death, it is the story of the life that preceded it.

In her most accomplished work, the preeminent novelist of the twenty-first century creates a world of suspended narration, bound by atemporality and infused by void. Rachel Cusk’s Arlington Park is a novel of supreme technique, principally in its use of narrative mode and point-of-view, one that remains the most perfectly executed of her works even in light of the Outline trilogy’s peerless innovation, and stands at the vanguard of her revolution in the novel form.(1) It is her approach to narration, propelled by exemplary mechanics and an inspired interpretation of poetic structure,(2) that both sets her apart from her contemporaries and unlocks her novels as works of literary genius. Arlington Park, as her greatest achievement, is thus worthy of extended treatment.

This essay will attempt a cogent, thoroughgoing dissection of the use of narrative mode in Arlington Park, demonstrating how Cusk achieves her novelistic goals via, primarily, point-of-view. As we proceed, we shall encounter the book’s interrogation of French Existentialism, which will provide us with our structure and navigational landmarks, revealing the novel not only as a outstanding achievement in narrational composition but also a profound statement on meaning and feminism, albeit in a rather idiosyncratic manner. It is imperative to note however that this essay is not an ‘existentialist reading of Arlington Park’; rather we set out to explore the connections between the brilliant Cuskian narrative mode and several of the broad metaphysical and ontological implications enumerated by phenomenological existentialism, and how this unity is both created by technique and offers an understanding of the world as the novel finds it.(3)

Arlington Park is interested in understanding how marriage, maternity, and the banality of the quotidian limits and shapes its central characters; as such, it seeks to render their worlds through an intimate connection with their surroundings. Each woman has her own response to this socio-psycho delimitation, and those different manifestations speak to the suffusion with which modern life circumscribes female possibility. These concerns inexorably entangle the novel with existentialist thought, and so by refracting our study of Arlington Park’s narrative mode through the prism of existentialism we will better understand how it envisions and realizes its narrative schema.

Arlington Park is at once a work of timelessness and urgency, a precise and poignant rendering of the individual consciousness of the women at its core and a disquisition on the obliteration of the self threatened by marriage and motherhood, an intricate artistic achievement and an interrogatory of existentialist angst. As with all of Cusk’s work, the focus of the novel and so necessarily of the criticism is on the sentence level, the how of form and narration, the peculiarities and sophisticated understanding of point-of-view. But in Arlington Park there is also found an immense concern with the what, with the (in)essentiality of life and the questions we hurl against existence. There is, in other words, a valiant attempt at narrative, and a fearless confrontation with time.

Neither Time Nor Meaning: Cosmopaghy and Consciousness

“You realise you’re waiting for something,” Juliet said, “that’s never going to happen. Half the time you don’t even know what it is. You’re waiting for the next stage. Then in the end you realise that there isn’t a next stage. This is all there is.”

Whether the earth or the sun revolves around the other is a matter of profound indifference.

—Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus

Arlington Park opens with perhaps the most accomplished scene in literature. To support this potentially-mad claim, we must first understand the manner in which the novel is constructed: its narrative and textual functions, meaning the book relating a series of fictive events, in the former, and ‘acting as a book’, as a crafted piece of art, in the latter.(4) The point-of-view of Arlington Park is, superficially at least, a typically heterodiegetic affair, centered on a rotating set of characters. (As always, perspective refers to the given character foregrounded by the narration, while point-of-view refers to the specific technical-mechanical approach taken by the narration in rendering (the worldview of) that character).(5) The narrative entity moves among several women on a rainy Friday in the titular London suburb, using various incarnations of the third-person to accomplish its goals. These goals are manifold—a precise rendering of their inner lives, an examination of semi-posh suburban family life, a peak into the void of contemporary motherhood—and require a narration with both flexibility and power. And so we come to those abilities of the narrative entity, the realm of point-of-view.

Requisite in all novels is an understanding of its own composition, or intra-textual rules. In heterodiegetic works, the narration begins from a primordial position of total possibility, what is often referred to as ‘omniscient third-person.’ Of course this creature is rarely actually given life in the novel (Tolstoy, perhaps, arguably something like Infinite Jest), but the point is it could exist; before a book written in the third-person (which, for our purposes here, is effectively synonymous with heterodiegetic narration, although in actuality the two are more like forest paths that occasionally intersect) begins, the narrative entity is unbound. From that sylph-like first word, however, the narration begins to construct its own prison. These are the intra-textual rules: methods of composition that, as they are enacted, foreclose the possibility of other approaches. This is most easily seen in homodiegetic (basically, first-person), for as soon as a character begins to narrate the events of the book, direct access to any other perspective is impossible. In heterodiegetic, however, the same phenomenon takes place. The narrative entity must delimit its own powers of narration, it must define terms, it must impose itself in a specific and delineated manner upon the world of its creation. Anything else is simply heresy.

So what do we see in the opening pages of Arlington Park? How does Cusk craft her narration to fit the needs and goals of her novel?

All night the rain fell on Arlington Park.

The clouds came from the west: clouds like dark cathedrals, clouds like machines, clouds like black blossoms flowering in the arid starlit sky. They came over the English countryside, sunk in its muddled sleep They came over the low, populous hills where scatterings of lights throbbed in the darkness. At midnight they reached the city, valiantly glittering in its shallow provincial basin. Unseen, they grew like a second city overhead, thickening, expanding, throwing up their savage monuments, their towers, their monstrous, unpeopled palaces of cloud.(6)

We begin with a comprehensive demonstration of narrative and textual functions, both of Arlington Park itself and of the novel as an art form. The narrative entity outlines its range, perception, and attitude in this evocative, ominous opening. With the coming clouds the narration creeps into the city itself—the city which will be the focus of the novel, more so than any one woman—and displays at once its overwhelming descriptive abilities and its idiomatic worldview. There is a characterization to this narrative entity, it has its own way of seeing, evaluating, and rendering. In short, it has opinions. It can also go where it likes, to glimpse people around the city and move freely between them. But it is not god, it does not approach the world with an all-powerful, objective understanding of events.

After moving through the center of the city, and offering the occasional glimpse of late-night revelers, the narration moves up the road towards the part of town that will be our principle locus, closing in on the soon-to-be heroines of the deluge.

To either side (of the High Street) tree-lined roads began to appear. In the rain these roads had the resilient atmosphere of ancient places. Their large homes stood impassively in the dark, set back amidst their dripping trees. Between them, a last, panoramic glimpse of the city could be seen below: of its eternal red and yellow lights, its pulsing mechanism, its streets always crawling with indiscriminate life. It was a startling view, though not a reassuring one. It was too mercilessly dramatic: with its unrelenting activity it lacked the sense of intermission, the proper stops and pauses of time. The story of life required its stops and its pauses, its days and nights. It didn’t make sense otherwise. But to look at that view you’d think that a human life was meaningless. You’d think that a day meant nothing at all.(7)

Our narrative entity is, by the close of this short opening chapter, asking in rich prose all the central questions of the novel to come. What did it mean, to tell a story of a life? What was the point, besieged by ancient clouds with their grey menace and impartial drift, to hopelessly divide human existence into comforting segments of fabricated routine? You’d think that a day meant nothing at all, says the narration of a novel set over the course of a single day. Ah, the bold defiance of purpose!

Note too the collapse of temporality, the decent into modernity evoked by the changing architecture along the main road, the early questioning of significance within an atemporal narrative. The narration begins Arlington Park with a haunting depiction of the rain that will mark the day to come—a narrative function aimed at grounding the reader and establishing setting—and a distillation of the existentialist dread that will pervade the lives of the characters as told by a cyclical, perspicacious narrative entity, textual functions towards theme and composition. As a literary descendant of the Dickensian fog that opens Bleak House, another titanic achievement of human story, the opening of Arlington Park is offering yet another element, an invocation of form and ancestry, an assertion of meaning in a meaningless world, a confrontation of time via the ephemeral power of narrative.

It is this assertion—meaning not only in the face of, but as resultant from, meaninglessness—that further signifies Arlington Park’s initial encounter with pointedly existentialist thought. Existentialism as fundamentally a doctrine of meaninglessness of life, as having no ‘greater’ purpose than that to which an individual assigns it, is reflected in this somber opening. The narration moves through Arlington Park as a highly subjective, yet impartial, observer, drawing the field of battle on which will be waged the struggle of significance against the inevitably of time, vividly depicted here by those minacious clouds laden with inescapable rain.

‘It was previously a question of finding out whether or not a life had to have a meaning to be lived. It now becomes clear, on the contrary, that it will be lived all the better if it has not meaning,’ Camus says at the midway point of The Myth of Sisyphus.(6) By this point in his essay establishing the school of Absurdism, Camus has well made the argument that it is this very meaninglessness which gives life its purpose—we cannot look to the cosmos to impose significance upon us, rather we must do it ourselves. Every action, then, is one of meaning. In the wake of the Nietzschian death of god, where existence has no superimposed why,(9) existentialism sees a comprehensible view of the world only through individual consciousness, devoid as life is of an omniscient narrator.

Arlington Park, then, demands an existentialist position of its reader if that reader is to subscribe significance to what they are about to read. There is something of Oran, Camus’ doomed city of The Plague, in the Arlington park as delimited by our mysterious, penetrating narrative entity. By establishing its boundaries, not only as a technical-mechanical elucidation of style and narrative mode but as a confrontation with the composition of the work itself, the narration at once establishes the path towards meaning for both its characters and its audience—the narrative and the textual function—in an embrace of ultimate meaninglessness. The novel will proceed on poetic grounds, it will imbue its world with substance and beauty via point-of-view as it creates it—in short, it will be a work of art aware of and concerned with its own artistic achievement, as it renders a timeless day in the lives of several characters facing that same confrontation within the narrative enclosure of the book itself. It would be hard to imagine, and this critic has certainly not found, a more perfectly constructed novelistic opening.

‘Sartre’s solution to the anguish of consciousness confronted by the brute reality of things is cosmophagy, the devouring of the world by consciousness,’ Sontag tells us in reading his study of the writer Jean Genet. Consciousness is at once ‘world-constituting’ and ‘world-devouring.’(10) To encounter an existence deprived of given meaning, we must look inward, to the wilds of the mind. Arlington Park is a work of consciousness-oriented fiction, one that wields its point-of-view to defy explore the inner worlds of each character. Cusk is unparalleled in her innovation of narrative modes towards accessing the self, and her dexterity is nowhere as accomplished as in the roving narration of Arlington Park. Juliet Randall is the first woman we meet, and surely the narration’s favorite. She wakes up in the morning, aware through the shroud of sleep of the pounding rain and remembering the dinner party she and her husband Benedict had gone to the night before.

She thought of their house, into whose kitchen alone the whole of the Randalls’ shoddy establishment in Guthrie Road would have comfortably fitted. What had they done to deserve such a house? Where was the justice in that? She recalled that Matthew Milford had spoken harshly to her. The lord of the manor had spoken hardly from amidst his spoils, from his unjust throne, to Juliet, his guest. And Benedict called her obnoxious!

What was it he’d said? What was it Matthew had said, sitting there at the table like a lord, a bull, a red, angry, bull blowing air through his nostrils? You want to be careful. He’d told her she wanted to be careful. His head was so bald the candlelight had made it shine like a shield. You want to be careful, he’d said, with an emphasis on you. He had spoken to Juliet not as if he’d invited her to his house but as if he’d employed her to be there. It was as if he’d employed her as a guest and was giving her a caution. That was how a man like that made you feel: as if your right to exist derived from his authority. He looked at her, a woman of thirty-six with a job and a home and a house and two children of her own, and he decided whether or not she should be allowed to exist.(11)

The world exists as Juliet sees it, and the meaning of things that occur is provided not from any omniscient being—be it god or narration—but from the manner of perceiving and meaning-making within the subjective mind of the character herself. Cusk’s principal method of achieving this effect, the foundational one to her novel as a whole, is free-indirect discourse, and as such is worth an additional look.

Later in the chapter, Juliet reminds Benedict that they’ve another event that evening.

Benedict looked displeased.

“Are we? Again?”

“We’re having dinner with the Lanhams.”

He frowned. He didn’t know any Lanhams. How could he be expected to know about Lanhams when another day awaited him at Hartford View, where giant sixth-formers threw tables across the classrooms and people got down on their knees before Benedict in the corridors?(12)

An excellent example of Cusk’s aptitude in free-indirect style and the type of character-specific colorization that might be called idiomatic narration, this passage demonstrates a protagonist’s conjecture as to the inner thoughts of another, non-perspective, character, as a cosmophagic method of novelistic creation—the world-as-constituted is ‘real’ only in the sense that Juliet imagines it as such, and therefore is equally liable to destruction. The latter half of the quote above is Juliet’s inner synopsis of her husband’s thoughts, complete with the self-serving hyperbole she would expect him to have towards himself (and while staying in the person and tense of the narration and Juliet, a marker of free-indirect).

These quotes, too, implicate many of the philosophical-thematic situations that will arise throughout the novel, including the challenges of motherhood and marriage, feminist implications of quotidian domesticity,(13) and the subject/object dichotomy of gender. In this way the section exemplifies another central compositional facet in Arlington Park: Cusk’s ability to deepen her work’s thematic concerns and critique of gendered literary conventions through its narration and specifically innovation in point-of-view. Following Wittgenstein’s limitations of language in sense-ably elucidating lived experience, Modernist cosmophagic narration achieves meaning beyond grammatical rules and linear plots, prioritizing words as individual units of resonance over conventionally coherent grammatical articulation of language. If interior lived reality is mimetically inaccessible via narration, then language (as words) is left to achieve ontological coherence aesthetically, and not didactically. This is the Modernist invocation of meaning, and in Cusk it is enacted principally through the immersive floods of idiomatic free-indirect discourse such as we have begun to see here. Arlington Park’s composition creates a comprehensive world, one that in turn is consumed by the expansive consciousness of each woman navigating the transcendent ordinary of her daily life, communicating a meaning that the reader knows more than reads, a cognitive intimacy reflecting the notion that “there are, indeed things that cannot be put into words. They make themselves manifest,” with nimble verisimilitude.(14)

In the opening passages we can also see a complete bleeding of existentialist entanglements; the novel is a comprehensive world, not a series of philosophical problems considered and retired in turn. In that way, even as we attempt the systematic in our approach here, we will never be wholly in the domain of one question at the exclusion of others. By moving firmly through Juliet’s consciousness, the opening implicates existentialist theories of ekstatic temporality, the passage of time as filtered through individual encountering with the world, that will carry throughout. “It is easy to understand why she is ruled by routine;” de Beauvoir writes in The Second Sex, “time has no dimension novelty for her, it is not a creative spring, because she is doomed to repetition, she does not see in the future anything but a duplication of the past.”(15) Arlington Park begins along these lines, beginning in darkness with its torrential downpour and then its most disillusioned character. It is the meaninglessness of the women’s lives that gives it meaning, as affirmed by the narrative mode. The rain which opens the book at once creates a narrative difficulty for the women to encounter, a textual greyscale, and an Aristotelian frame to the narrative itself. Departing from Plato, who in his world of forms sees something greater and more solid behind life as we can make sense of it, Aristotle posits an existence with no backstop, and that the frame surrounding a work of art—its, we might say, narrative—is that which gives it its mimetic power. The characters are entombed within this rainy Friday, itself a liminal space between week and weekend, between leisure and responsibility, between school and home, as a day that represents all the days, past and future, of the their lives.

It is the depths to which Cusk explores the these lives, the differences she is able to show between them, even as superficially the same—achieved fundamentally via point-of-view—gives this essentially apurposed existence, one of routine and work, childcare and rote dinner parties, loud men with louder opinions, stagnant careers and stale shopping malls, a significance and power that performs through expert narration the existential transubstantiation of meaninglessness into meaning.

A Place of Unpredictable Danger and Occasional Savagery: The Dialogic Consciousness of Motherhood

She wanted to shield her, from the bullet of an ordinary life.

Ordinarily, maternity is a strange compromise of narcissism, altruism, dream, sincerity, bad faith, devotion, and cynicism.

—Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex

That the women of Arlington Park require meaning to be infused into their lives at all is a situation of quintessentially Cuskian audacity—they, of course, are mothers. As we shall see, the novel establishes a complicated position on feminism, but one that leaves doubt as to where its sympathies ultimately lie. Much of Cusk’s career (for the artistically better and commercially worse, perhaps), has considered the price of marriage and motherhood in contemporary society, and she has never hesitated to struggle openly with the challenges of each. What this means for Arlington Park as a work of feminist ethics we will consider later on; for now, we stay on the sentence level, and explore the women’s internal relationship to their children as well as the narration’s wielding of the wonderful device known as dialogic consciousness.

Juliet is up and about; as Benedict prepares for the day to come, she sets about wrangling the children. Her daughter Katherine has come to inform her that her brother Barnaby is refusing to get ready up in their room. Juliet comes in to find him naked on a mountain of bedclothes, playing make-believe with a toy horse.

Up and down went the horse, obvious to all but the gods of carefree cantering, so preferable to those of Juliet’s ugly autocratic regime. She began to pick things up off the floor. She worked closer and closer to him, and when she got close enough she grabbed his bare arm and yanked him off the mountain.

“Get dressed,” she said.

“I was playing,” he protested.

“I don’t care what you were doing. Get dressed.”

She gathered up all the bedclothes and hurled them onto the bed. Oh, how differently she felt when it came to Barnaby! How punitively she yearned to have him in uniform, to have him straitjacketed! When he played, as he was playing just now with the little horse, it felt as if he were stealing something from her. She started to make his bed.(16)

The vulnerably of the naked child permeates the scene with a certain perverse pathos while the language selects its artistic elegance in vocabulary that perfectly aligns the narrative and textual functions. Up and down goes Juliet’s life, shackled to her role as the obscure, autocratic god lording over her children’s lives. The descriptors are yet more instances of free-indirect, as the narration pulls from Juliet’s (guilty?) consciousness the words her son would use towards her, should he have her command of language. And then comes the crash—as Barbary tumbles down the mountain the narration moves closer to Juliet’s mind, capturing the intensity of her feelings towards him, even as she continues to straighten up and make his bed.

We will keep Juliet’s tempest in mind as we greet Amanda, the second character to appear in the novel. Running errands in the morning before some of the women come round to her house for coffee, she exemplifies Cusk’s ability to change speeds, vary the feel and texture of her narrative method even as it progresses as a unified whole. Amanda is a calculating woman, whose encounters with the world around her implicate phenomenological intentionality, as will be seen in the next section. However she too faces exasperation caused by her son, Eddie, who accompanies her to the butchers and asks aloud an innocently rude question regarding the shop assistant’s deformed hands.

Of all the members of her household Eddie was the one who most often led her into the senseless, run-down parts of life. Two or three times a day he put her close to the concept of failure and meaninglessness. As she could think of no appropriate answer to his question, she decided to ignore it and wait for the embarrassment to pass…

She gave [the assistant] the money, while Eddie stood and fingered the glass so that the spectacle of dismemberment behind to seemed to expand itself, to incorporate him. She saw his parts arrayed on metal trays, in fans and pyramids of flesh fingered with parsley…

[After Amanda tells Eddie vaguely about birth defects caused by thalidomide.]

“Did the doctor want you to take it?”

Eddie sounded concerned at the idea that his fate had rested, even momentarily, on the precarious peaks of his mother’s mist shrouded judgment. Anything could happen up there: it was a place of unpredictable danger and occasional savagery…

Something raised itself swiftly in her like a club, a desire to disclose to him the truth of herself. She wanted to hammer him over the head with it until his understanding of her was compete.(17)

For Amanda, motherhood is a constant risk of meaninglessness and paths leading to needless diversions from her ordered life, minor-yet-unwanted irregularities in the structure of her day. For Juliet, conversely, motherhood is chaos, absurd, emotional, uncontrolled. She awakes and realizes she has lost the sense of her life and she has been thrown amongst others. These two quotes demonstrate that it is not so much the external responses between Juliet and Amanda (which the discerning reader will note is not all that different) that differ but instead the manner of presentation.

The effectiveness of Arlington Park’s narrative mode is illustrated in this juxtaposition in each woman’s reaction to their unruly son. The scenes between Juliet and Barnaby are far more technically raw, bleeding her worldview into the scenic narration with an intensity not found in Amanda’s scenes, who is a far more stoic figure, possessing a detached sang froid. The latter’s clinical nature is expressed in the greater narrative distance in the second quote, especially the greater use of Cohnian psychonarration (although not absent the type of free-indirect speculation on foreign psyches seen with Juliet), illustrating the contrast in their characters, and the varying ways motherhood can invade and destabilize the subjectivity of each woman. Thus while they share a reaction, the rendering of each is crafted in a manner to imbue each scene with the character’s mind and personality, a hallmark of the Cuskian point-of-view.

Amanda and Juliet have on balance the same feelings towards their son; an estrangement that complicates their basic love for them, and a wish to exert the authority they know will soon enough begin to diminish over them. In this way they are connected, and an example of what Violeta Sotirova terms dialogic consciousness,(18) the unification of disparate mental states by an insightful, mechanically gifted heterodiegetic narrative mode. The potency of this technique stems from its ability to weave various perspectives within a consciousness-forward novel into a tapestry of idiomatic narration. By uniting the responses of the women to the fundamental questions of motherhood, marriage, and meaning, Arlington Park is able to offer a far more profound insight than can be achieved in any one perspective, even as the point-of-view varies between them in responding to their individual, subjective sense of self.

It is for Juliet that this sense of self is the most elusive. She was gifted and accomplished in school, and had assumed she would accomplish something more profound than a return to Arlington Park as a married mother of two. Her exceptionalism, as she refers to it, represents a duality at the core of her mental state: she is (or at least was) in possession of intellectual gifts that mark her as special while simultaneously, by their being unfilled, cast her down in some ways lower than the other women. Later on we will explore this aporietic state in greater depth; for now let us examine how her view of herself—the destabilization of which opens the novel—is deepened by the narration’s implementation of dialogic consciousness.

The most physically notable thing about Juliet is the extraordinary length of her hair; the narrative entity tracks her fixation on it throughout the opening chapter; Benedict loves it and is constantly attempting to interweave it in his fingers, her mother disparages its impracticality, her students identify her personality with it. The damp morning which suddenly seems to encapsulate her entire life sees the end of this totem of her personality, and by extension the exceptionalism she sees as now dead. At the end of the chapter Juliet impulsively goes to the hairdresser and has it cut short, an attempted resolution of her internal paradox.

This has consequences.(19) A more direct interpretation of dialogic consciousness comes near the end, during that dinner at the Lanhams’ by which Benedict was so perplexed. The final chapter, having taken up Christine Lanham’s perspective in a slightly more chaotic point-of-view (fueled, in part perhaps, by wine and fatigue), sees a return to the topic of Juliet Exceptionalism, now from the outside.

And Juliet had finally cut off that terrible hair! She’d had it since she was a schoolgirl, when Christine first knew her…She’d gone about with her that hair down to her waist as though it was against her religion to cut it. She was all clever and superior in those days.(20)

The dialogic affect to consciousness presentation caused by these views of Juliet—one from within, the other from without—help to triangulate and stabilize the internal view of her we get early on, and reinforce the underlying composition of the novel. It is a foundational aspect of the narration, much like the world it renders, that the truth is got at intervals and by degrees, never straight on and direct. The cross-perspective movement along interior lines heightens the mimetic quality of the narrative, as the reader pieces together events much in the way found in life, though gossip, aside, and rumination. For the lives of the women in Arlington Park are at once mundane and multifaceted, and the novel understands that only by plurality can we gain perspective.

“The little girl,” de Beauvoir writes in The Second Sex, “is more wholly under the control of her mother; her claims on her daughter are greater…The mother does not greet a daughter as a member of the chosen caste: she seeks a double in her. She projects onto her all the ambiguity of her relationship with her self; and with the alterity of this later ego affirms itself, she feels betrayed…She is doubly jealous: of the world that takes her daughter, and of her daughter who, in conquering part of the world, robs her of it.(21) While several passages from “The Mother,” in Volume II, resonant with these moments in Arlington Park, this selection will serve as representative. We have seen some of this conflict already; let us study two further passages that more directly speak to de Beauvoir’s conflicted state.

Juliet had wanted to keep Katherine for herself, but instead she’d had to surrender her, as though called upon to make a sacrifice to her own implacable gods…Until that moment the possibilities for Katherine had seemed endless…Now, though, she was different. She knew she was a girl. She returned from school full of a kind of programmatic agony. Her soul was in training. They had told her what she was, and now she knew.(22)

Approximately one hundred and fifty pages later, Maisie Carrington, while getting ready to attend the Lanham’s dinner party, confronts similar feelings putting her two daughters to bed.

And yet there was nothing in the world she wanted for them, nothing in the whole world excerpt for them to live, like two stolen bars of gold in a carpet bag, within her possession. There was nothing in the world they needed, only for her to believe they belonged to her.(23)

The technique allows for the complexity of both woman’s feeling towards their daughter(s) to be explores in full: the narration renders their interiority with more polish and coherent rapidity than would be achieved in a closer technique (such as some approaches we will see later on), while still infusing each passage with the emotional-cognitive worldview that creates connection to and understanding of both characters. These moments are not narrated from above—telling us how Juliet and Maisie feel in a Victorian detachment—nor from within, submerging the reader in the free-associative wilds of pure consciousness. Rather the narration seems to be alongside each heroine, translating her thought process and intricate emotional state into something at once cogent and profound.

At the same time the characters’ interior lives are united though the narrative’s employment of dialogic consciousness, intensifying the ontological crises presented by motherhood as a fundamentally ambiguous state of being. For the vast differences between Juliet, Amanda, and Maisie—differences that are rendered via point-of-view—the state of motherhood confronts them in analogous fashion. In this way the novel creates momentum though form and unity through technique, freeing itself to render with great verisimilitude a day in which nothing especially happens with remarkable elasticity and resonance.

A Bleeding Without Blood: Intentionality

She could evoke, in other people, a type of self-consciousness, a reconnection with themselves.

Mardi:

Rein. Existait.

—Jean-Paul Sartre, La Nausée

Throughout that day of profound nothingness, the narrative mode bends the world to the subjective realities of its perspective characters using, as we have seen, a sophisticated technical-mechanical understanding of point-of-view. It is this bleeding of the inner lives of the characters with the scenic narration that toppled the Victorian-Edwardian novel’s centering of external acts and ushered in the Modernist revolution towards a verisimilitude of the mind. When Virginia Woolf—not coincidentally, Cusk’s most direct literary ancestor—asks ontological questions about the nature of the novel,(24) she sounds off an artillery barrage that reverberates though Arlington Park’s privileging of the idiosyncratic nature of reality. Life, we have learned since Mrs. Brown’s fateful train ride through the English countryside, is all about how one sees it.

This collapsing of the Cartesian duality sees its philosophical expression in Husserlian phenomenology; as Sartre writes of his revelatory encounter with it, ‘Consciousness and the world are given at one stroke: essentially external to consciousness, the world is nevertheless essentially relative to consciousness.’(25) In the Sartrian account, intentionality becomes the manner in which the world is apprehended by consciousness;(26) another term for such a notion might be idiomatic narration.(27) We observed something of this earlier, with the ekstatic temporality that bends the traditional textual-temporal relationship around the mass of consciousness that predominates the narration’s focus. We see it more fully first in Juliet’s fretful morning, thanks to her husband’s hopeless affections.

Behind her, Benedict touched her hair. She shrank from the feeling of his hand. She turned around so that he couldn’t touch her anymore and his hand was left suspended in midair. There was his face, smooth and red-cheeked like a baby’s face, with his little knowing eyes in the middle of it. In his smock, with his red cheeks and his eyes that were like the twinkling eyes of an old man, he looked like an illustration from a fairy tale. He looked like a woodcutter, or a shoemaker. She did not want to be touched by a shoemaker from a fairy tale. She was prepared to acknowledge his magical qualities, but she didn’t want him touching her.(28)

This passage shows the lengths to which the narration is prepared to go in aligning itself with its characters’ worldview. Juliet in her slightly hungover annoyance sees her husband as a ridiculous character from a children’s fairy tale and so he becomes one in the narration.

Let us next move to the very end of the novel, where Benedict Randall is again taken as the object of one of the women’s consciousness, to see this technique drawn out to an even greater extent. Christine Lanham has taken solace in the wine as she hosts the cumulating dinner party, and the narration gradually moves closer to her worldview, which includes seeing Benedict as “a funny little bloke. He looked like a little elf, with his pointy ears and his red cheeks and his sparkling eyes.”(29) Besides an expert display of the dialogic consciousness examined above, uniting Juliet’s and Christine’s views of Benedict across more than two hundred pages, this description sets up the complete realization of narrative-character alignment in point-of-view.

What about love?” said the elf.

She thought she hadn’t heard him right. “What about it?”

“Is it important? Does it have any importance, in all this future-building frenzy of activity?”

Christine lifted her glass and saw there was nothing in it.

“I don’t know why you’re asking me,” she said.

He shrugged. “I thought you might know, that’s all.”

She put her glass down on the table and it fell on its side. She watched a last little dark drop, like a tear, run out and over the rim.

“You’ve got to love life,” she said blearily. “You’ve got to love just—being alive.”

“But how will anyone know you loved it?” said the elf.

The room took a great tilt. It turned on its axis with all its ill-fixed clutter, its plates and people and furniture, its painstaking, ill-fixed record of time. Christine righted her glass, but the room remained tilted.

“Why would anyone need to know that?” she said.(30)

How fully we are within Christine’s world. Sontag’s cosmopaghy is on display throughout this moment, such titanic notions of love and art are assembled and demolished between sips of wine. In keeping with the simultaneity of existentialist precepts as they appear, we see much of the assertion of meaning in the face of meaninglessness as seen earlier and several of the questions towards morality to be more carefully considered below. But this section is most vividly an example of novel’s invocation of ontological interiority, a creation of the world by the mind.

Amanda, with her determination and purpose, is the strongest-willed of our heroines and thus the best representation of phenomenological intentionality in the existentialist sense.

Outside the butcher’s she commanded the localised bureaucracy of the street to yield to her: immediately a car prised itself out of of the parking bay right in front of the shop and went slouching and blinking off down the road, dismissed. Sometimes Amanda was able to evoke perfect subjection in the world around her and sometimes she was not.(31)

We are again outside the butcher’s; time has no meaning either in Arlington Park or in voluble criticism thereof. Having observed Amanda’s ongoing struggle to keep at bay the chaos threatened by her son Eddie, let us investigate how this scene exemplifies her larger (self-)orientation towards the world—and the narrative entity’s embrace of it. This first passage shows not only an actual example of external events taking their shape from her thought, but the use of free-indirect style renders the moment as an admixture of her syntax (which casts her as the ruler of a chaotic world) and the scenic movement, in idiomatic narration.

After two full pages are taken to relate the flawless parking procedure, during which Eddie swears at the car that momentarily blocks their path, Amanda sits for a moment in the car, thinking that ‘if she were not married, it would not have been required of her to go to the butcher’…

She imagined that if she were alone she would have eaten only food that was white. A vegetarian friend of hers used to say that she never ate “anything with a face.” Eddie had a face. Amanda looked at it in the rear-view mirror.

“It isn’t nice to swear, Eddie,” she said.

Then she got out of the car.(32)

The time-to-text ratio indicates what Amanda—and by extension the narration—find to be of interest, while the free-associative movement between her friend’s aversion to food with a visage and her son’s face is an expert example of transition between external and internal that defines Arlington Park’s narrative mode. This is that which Modernism hath wrought.

But Cusk is a revolutionary in her own right, and her understanding of Modernist narrative mode evolves into an entity all its own. By the time she gets home Amanda is hard pressed for time; the women—whom Amanda had long tried to get over for coffee—are nearly there. She finds solace in her kitchen, which is so large and grandiose as to have acquired its own reputation around Arlington Park.

Sometimes Amanda remembered the quavering places that had stood where her kitchen now was: the sinister little toilet with its tiny window of marbled glass, the cold, abject washroom, the austerity of the original kitchen itself, with its air of denial, almost of castigation—there has been a helplessness to these rooms that at the time had inflamed the Clapps’ urge to destroy them, but which now occasionally caused her to wonder what had become of them and what their true nature had been.(33)

A few pages on from this bellicose reminiscence, the women have arrived.

Today the women standing in the rain outside the school had looked lost, unfocused, like a a demoralized troop of soldiers in the middle of a long, obscure campaign. She had discerned in them an unusual vulnerability, an exposure of flank, and she was right: for the first time, her offer of coffee aroused their interest, or at least silently generated the possibility of obedience.(34)

The idiomatically blended yet mechanically clean narration in these passage is a Cuskian innovation par excellence. Human connection is conquest and survival. Amanda’s worldview utterly dominates the fictive world, to the point in the second section of (potentially) exercising an agency over the actions of the other women. In High Modernism this approach is realized though mechanics of disorder, what Cohn calls quoted monologue. Here, however, in keeping with Amanda’s structured sense of self, the world is rendered with strict precision and movement, even as her antagonistic relationship with reality, her loneliness, and her isolation are immediately available on the page. Her manner of apprehending the world, then, is the manner in which she and it are brought together.

Jean-Phillipe Deranty notes that for existentialists, aesthetics connect the metaphysical and the ethical in shaping the manner in which a consciousness intends towards the world.(35) “Thus the reflective consciousness can properly be said to be a moral consciousness, since it cannot arise without at the same time disclosing values. It goes without saying that I remain free, in my reflective consciousness, to direct my attention towards these values or to overlook them.”(36) Here we have—in addition to a caveat that seems to elide an ethical imperative, to which we will resoundingly come later on—a conception of values that stem from one’s manner of seeing the world. Amanda seeks to impose order and regularity on her surroundings, and in a phenomenological sense it is her value system that shapes her manner of doing so; in turn this shapes the narration’s approach to its work.

In this sense intentionality is a key feature of Arlington Park’s point-of-view: the narration is only interested in that what the character is interested, and only that which the character observes exists in the book. Throughout the scene in which Amanda prepares for the women to arrive, external events—so ostensibly monumental as the death of her grandmother—occur, but they do not happen. There is no textural (or textual) change in the fabric of reality when it encounters significant external occurrences unless they are deemed to be significant by Amanda herself. Meaning is only given to that which her mind creates.

This lack of interest is shown in full relief by the immense consternation Amanda feels when Liz Connelly’s young son Owen draws on her cream-colored sofa in red felt markers.

Soon they would go; she would cause them to go. First, she would cause Eddie to let go of her legs. Then she would package the Connellys up and put them out in the rain, with the red stain remaining as a reminder of this day, this day of her life in which all the other days seemed to be coming together and showing themselves at last.

Then she would cook the mince.(37)

This clinical response (which comes immediately after Eddie hugs her round the legs upon learning of the death of Amanda’s grandmother), invoking the running motif of red and white that builds throughout the chapter, from the flesh and bone of the butcher’s meat to the disaster with the couch, is an elegant parallel to the overall poetic approach. It is the ordered world of her sofa, not the death of her grandmother or the gossip over their husbands carried on by the women, that receives both attention and ire from the narrative entity. Even at her most destabilized, however, Amanda causes the world to be seen in a regimented path back from chaos. Her narrated world remains intact, a bleeding without blood.

We have discovered then a synthesis between a Sartrian (realist) interpretation of phenomenological intentionality and the quintessentially Modernist foregrounding of a verisimilitude of the mind taken up by Arlington Park’s narrative entity. The manner in which a character’s interiority is rendered on the page, through a poetic (stylistic and narratological) conception of narrative mode, is the narrated world. There is no gap between, to use the preeminent example, Amanda’s subjective interpretation of the fictive situation and the situation itself; there is no ‘external reality’ to which the reader might retire. That which is, is. Je pense, donc c’est.

Domesticity of the Apori(a/e)tic: the Other, the Object, the Mother, and the Self

It took away your anonymity, perhaps forever, and wherever you went, there you stood, between yourself and the world.

But the very circumstances that orient the woman towards creation also constitute obstacles she will often be unable to overcome.

—Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex

Mais si je suis, je suis qua que? Earlier we took note of the oppositional duality present in Juliet’s idea of herself and (what was) her great potential. In this sense her intellect, her love of literature (the apogee of which these days is merely her leading the Literary Club on the last Friday of the month, the only fact which allows her to escape the mad dash across the park to collect Katherine and Barnaby at their school which is otherwise a daily occurrence), remains an aporia, the transcendent possibilities she had suspended in static opposition to the timebound facts of her life.

She had never expected to find herself here, where women drank coffee all day and pushed prams around the grey, orderly streets…She had thought she would be in a university department somewhere, or on the staff of a national newspaper. Other people had thought so too. At school she had been the exceptional one…

It almost made her laugh now, to think of it. A woman a hundred years ago know her life would be over the moment she got herself pregnant. But Juliet had thought it required a degree of cleverness, that there was something difficult about it. For a while she praised the idea of a house and a husband and children, as though these things were uncommon, as thought they represented some new refinement of human experience. Then she got them, and the feeling of lead started to build up in her veins, a little more each day.(38)

It is arguable that for Juliet, the epiphany of failure she experiences at the close of the book’s first section is that her life has amounted to motherhood. This is a bold statement made by the novel, one that contemplates its larger framework of narrative amorality. de Beauvoir’s phenomenological approach to femaleness, which as Karen Vintages notes moves the ontological situation of a woman to a locus within her own subjective approach (understanding) to objectivity (the facts of her bio-socio-cultural context), means that motherhood, and its ability to define her self, is driven by that self.(39) Juliet, then, encounters her crises of meaning when faced with the fact of her motherhood—not as a rejection of her children, but as a comprehension of her implication in her ongoing self-definition of the self. She had one time had been exceptional, she had been defined precisely by not that which she saw around her in Arlington Park—and she has now become defined by that very same mode of living. Juliet is defined by that which she is not, by that which she saw herself to not be. Her narrative has resisted a dialectic synthesis of past into present; she remains suspended in the aporietic, defined by what she might have been. In this way her former exceptionality has left her clashing with Kierkegaard’s (in)authenticity, culminating in her having her hair cut as method of fleeing from her former self, one full of possibilities now unrealized and so posing a threat to her current existence. ‘Life itself is nothing until it is lived; it is we who give it meaning, and value is nothing more than the meaning we give it,’ Sartre writes.(40) For Juliet, the meaning is suddenly caused by her own, imminently unexceptional choices, ones that for her are in irreducible tension with the vision of her past self she vividly recalls.(41)

For de Beauvoir, phenomenology renders women as a gendered situation, positioned in a secondary status with an internalized meaning.(42) ‘She is determined and differentiated in relationship to man, while he is not in relation to her; she is the inessential in front of the essential. He is the Subject; he is the Absolute. She is the Other.’(43) In Arlington Park, the women exist in relation to their husbands and children, while actively thinking about them far less than might be expected. The narration, as we have seen, emanates from their interiority; the characters do not need to constantly think about their embodied experience, in the de Beauvoirian sense, because it is their default mode of existence. In this way the poetics of Arlington Park, operating at a structural level, implicate the feminist ontology elucidated in The Second Sex.

However, when the narrative does encounter men in the wild, we find a striking depiction following the existentialist distinction between the object-body and lived-body. Juliet, moments before the aporietic crises instigated a collapse of her sense of self, walks her children to school. Along the road are cars, stopped.

Their lights glowed like devilish pairs of eyes. The rain fell on their impervious metal roofs. Heat came in great sheets of steam off their armored bonnets. The arms of their windscreen wipers went back and froth, back and forth. In each one sat a man in a tie and an ironed shirt, warm and dry, his suit jacket hanging from a peg beside the door. These men glanced at Juliet as she went by, one after another through their beaded windscreens. She went along the grey pavements holding her umbrella. Katherine was holding her hand. Barnaby was walking behind, with his hood up and his hands in his pockets. Juliet carried their lunchboxes and their schoolbags. The children were wearing Wellingtons, but the water had soaked Juliet’s tights nearly up to the knee. She labored along the pavement, burdened, bedraggled, while the men looked at her from their cars.(44)

This virtuosic display of pas de sense operates along both paths of translation.(45) Again the narration infuses the moment with a stark worldview via repetition, syntax, and diction; one need only compare the difference in orientation-to-the-world between this passage and that of Amanda’s Napoleonic conquest of life to grasp the full effect of Arlington Park’s masterful point-of-view. Juliet is an object, observed and watched by the men from inside the subjectivity of the car. She must to wear tights in order to look suitably feminine at her workplace even as she’s soaked though by our meteorological framework. As she struggles along the men from the cars check in her, ensuring she is fulfilling her socio-cultural obligation—taking her children promptly to school while dressed appropriately. The technical-mechanical blending of the narrative entity’s scenic description and Juliet’s idiomatic worldview work as a tandem in showcasing the absurd, contingent situation inherent to her status woman and mother.

Before leaving the school Juliet overhears the other women making plans around coffee.(46) Despite her obvious proximity, they don’t include her. ‘In its way it was a religious ceremony, and she was not of their religion. With her job, her Ph.D., her air of bitterness, she was an outsider.’(47) We know by know of course that this is Juliet’s accounting of the situation, bled into the narrative moment. She recognizes herself as l’etranger, a few pages after enduring the stares of the commuting men. Juliet, the narrative entity’s favorite daughter, battles with both authenticity and alienation, moving through the spaces of both Object and Other.(48)

The aporiatic suspension caused by the confrontation between identity and motherhood is most richly explored in the narrative’s encounter with Solly Kerr-Leigh, the most fertile of the women of Arlington Park. A mother of three with a fourth on the way, Solly comes up with the idea to let out their spare bedroom to exchange students, creating space for the narration to challenge the novel’s temporal construction while making its sharpest statements on motherhood and the self. Solly, besides having the most children of any perspective character, is also the one women for whom motherhood seems to be the most natural;(49) nonetheless she struggles to demarcate her position to the world.

Solly had felt before the way everything altered just before a child was born. It was how she sometimes thought it might be to approach death…She was depleted, of some aspect of experience, of history: it was torn from her, like the wrapping paper from a present. Generally she believed that this was what she had been born for. She was grateful that she has been able to put herself to such prolific use. And the children gave so much back to you, of course. She was like a sack stuffed with their love and acknowledgment, lumpy on the outside but full, heavy with interior knowledge. It was just that sometimes she tried to think about the past and couldn’t. She couldn’t locate a continuous sense of herself.(50)

The use of narrated monologue is on grand display throughout as minute shifts in point-of-view render with a high degree of fidelity motherhood as an approximation of self. Along with the Heideggerian run towards death that’s flirted with at the paragraph’s opening (not to mention the de Beauvoirian internalization of meaning), there is a richness and complexity of emotional-cognitive interiority rarely found in intermediate-range heterodiegetic fiction.(51) Note the one-line shift from indirect to free-indirect discourse (‘and the children gave so much back to you, of course’) as the narration captures Solly’s rationalization, or perhaps less cynically assimilation, of the loss of her history and individuality.

Moving from the lexical to the sentence, the narration has other tricks of the trade to ply.

She wanted to feel a boundary with the world, before she was diffused entirely into flesh relatedness. The spare room appeared to her as the place where this boundary could be established. As her point of entry from the lost simplicity of life, so it was to be her means of return from all this marshy expansiveness towards a new independence. Once she’d installed a television up there, apparently, she could expect to get eighty pounds a week for it.

Martin thought it was a marvelous idea.

“What about the children?” he said doubtfully.(52)

The technique is one the narration returns to often in the section; as time becomes more complicit in the destabilization of Solly’s world, transitions such as this one mirror the collapse between her external and internal world. The moment is preceded by a long stretch of blended narration providing the history of letting the room before, with a sudden elegance, sliding into a scenic conversation at the dinner table. The section spans an elusive length of time, covering three students renting the upstairs room, before aligning the birth of her fourth child with the day the other women have been experiencing. This atemporality, keeping thematically with some of what we saw above, aligns the narrative and textual functions: Solly drifts through her pregnancy while the novel is formally caught in a timebound timelessness, both reader and character somewhat attenuated by temporal movement even while feeling an anchorless sense of time caused by the movement and structure.(53)

This effect is achieved on a larger scale as Paola arrives, the picture of Italian elegance and femininity who represents, to Solly, everything that motherhood has denied her.(54) Solly is out in the garden with her children when a song stirs up a wave of memory.

She was eighteen or nineteen—she remembered wearing jeans so threadbare her slender knees showed through, sitting cross-legged on the floor…How strange that she should have forgotten it! How strange that it should have been there all along, this memory, alive and intact but buried, hidden, like the child in her belly was hidden!

It was then, just as Solly brought forth this naked recollection, expelled it into the light, that Paola rang the doorbell…It was so beautiful! It was so beautiful and yet so lost, so utterly lost and unavailing!

The doorbell rang again.

“Mummy!” Joseph shouted crossly, pointing towards the house.

With shaking legs, Solly went lumbering inside and down the passage and opened the front door. A woman stood there with a large suitcase.

“Solly Curly?” she said

“Kerr-Leigh,” Solly automatically amended.

It had required a certain bravado, all those years before, to insist that her name be hyphenated with Martin’s rather than replaced by it. That was what she thought marriage should be: the state of hyphenation. Yet most of the people they knew pronounced it as the woman had just done, as one word with the emphasis on the first syllable. That syllable was Martin’s: it seemed a particularly insidious form of discrimination.(55)

Her present overwhelms her past, not only in the use of free-indirect to capture her emotions about the memory itself (couched in the language of birth, as that topic predominates Solly’s thoughts), but in fictive present scenic events cutting through her reflective moment as the demands of motherhood and quotidian domesticity sever her connection to her past. Of course it is Paola, who becomes Solly’s foil and ally, that mispronounces her name. In the twenty-first century, her identity is lost not by the tyranny of her husband or the institution of marriage as-such; rather it is the necessity of language, the simple, bare facts of the everyday, that work to whittle down Solly’s individuality. The machinations of the world are the enemy, and as the narration observers, thus far more insidious. It is her very name that leaves her in the state of aporia, an ongoing and ineluctable opposition of self—even as one side threatens always to overwhelm.

The narration thus destabilizes the readerly sense of order and time as it as been established up until this point in the novel while rendering Solly’s fading individuality and sense of self late in her pregnancy. Solly perhaps more than anyone feels within the subject-object duality of meaning, and her relationship with Paola, whom Solly assumes to be childless, allows the narration a fitting area to explore this dyadic while also capturing their respective narratives within the larger whole. The section closes with Solly going into labor and discovering that Paola has a young son in Italy, causing a ‘great bewildering wave of knowledge’ to pass over her, just as the applauding rain from the opening returns.

By its end, the chapter fully realizes the invasion of the internal by the external, the insistence of the past upon the present. The clean, white room upstairs is the conduit to Solly’s timeless existence that amiably understands motherhood as at once fracturing the link with her former self and approximating her ever-changing identity into which she might assume. The Woolfian bursts of free-indirect style, often as if taken from Mrs Dalloway itself, enliven her memories to elevate them above the quotidian repetition of life.

As a mother Solly has no past and no future. Her husband loops to and from nondescript Reading for work while Paola emerges from exotic, sensual Italy with her svelte form and tragic history intact, but for Solly there is an only ever-present now, what we might call a narrative maintenant perpétuel,(56) occasionally harassed but never truly threatened by the memories of the person who once lived her life. By the end of the chapter we find that motherhood can never be truly synonymous with freedom, even if it may allow a looser interpretation of imprisonment, as Solly is astonished over Paola’s having a son. Because this glimpse of something beyond the monotone repetition of days cannot stand in the world of Arlington Park, and Paola with her personhood and her freedom must return to Italy.

A Slight Pause Before Death: Freedom and Condemnation

She had imagined herself freed, of human relationships themselves.

Man is condemned to be free.

—Jean-Paul Sartre, Being and Nothingness

We, however, remain in England, where there is death. That notion of absolute freedom is a central tenet of existentialism, circumscribed as it may be by one’s situation. Arlington Park, with its incisive narration that brings the external world onto the plane of internal subjectivity, implicates and perhaps challenges this concept in looking at the condemnation of motherhood.

Before their final moment of revelation, Solly and Paola are some time in each locating the boundaries of the other. Sometime after her arrival, Solly asks Paola how she ended up in England; it seems there was a man, and when he left, Paola decided to stay.

Solly was seething with questions. It was strange: in Paola’s presence she felt herself to be a failure, yet a part of her believed that a woman of thirty-four with no husband or children was the greatest failure of all. It was a kind of unstoppable need for resolution that grew from her like ivy over the prospect of freedom and tried to strangle it. She couldn’t bare the idea of loose threads, of open spaces, of stories without endings. Did Paola not want to get married? Did she not want children, and a house of her own? She sat there in her white sweater, delicately eating. Solly, a sack stuffed with children, a woman who had spent and spent her life until there was none left, sat opposite her, impatient for more.(57)

Cusk’s use of free-indirect style in this passage is some of the most effective in the novel. The repetition of ‘failure’, the interrogatory tone, the imagery of strangled freedom and loose threads of life, all work to position Solly’s raw interiority as one that reflexively recoils at Paola’s (presumed) liberation. Freedom is the enemy of motherhood, a usurpation, a threat to Solly’s understanding of the woman-as-maternal and, by necessary extension, herself. There is a demand for narrative—‘stories without endings’—that can only be achieved by motherhood; there is no conception, in Solly’s accessed mind, of another suitable resolution. As much as Solly may be aware of this inflexible worldview (which, depending on one’s interpretation of the passage, appears to be the case), it is her, one might say, nature. Whatever the extent that Solly may directly oppose the Sartrian ontological positioning of women as having no a priori ‘essence of motherhood,’ she certainly understands her role as a mother to be fundamental to her being.

As we shall see in the final section, Arlington Park does not make narrative assessments of its characters; it is perhaps the novel’s defining compositional trait. Nonetheless there is a sense that motherhood sharply delimits the boundaries of the possible for women, expressed most powerfully in the instinctual asperity towards an independent, unattached that Solly feels while looking forward, generationally, in her definition of womanhood. In the novel’s final act, the narration reverses, inciting the possibility of an inherited death of freedom.

Preparing to host the long-awaited dinner party, Christine receives a telephone call from her mother, Viv. After a discussion on the risks of chicken, the ‘filthy bird,’ Christine elicits a confession that her mother has given up her bridge playing, an activity she took up after the death of her husband, Christine’s father Larry.

Christine was rooting out plastic bags of sals from the fridge and tossing them on to the table. Then she took out a bottle of ready-made salad dressing and a half-full bottle of white wine, slammed the fridge closed with her hip, and, with, the phone still wedged beneath her chin, pulled the cork from the wine bottle with her teeth.

“Look, Mum,” she said, tipping the wine into a glass, “I know it’s not easy being on your own. He’s only been dead six months. Just give it a bit of time.”

“People always tell me that,” said Viv. “I say, what do I want to give it time for? I don’t have much time to give. Your father took most of it.”

Joe appeared in the doorway and looked at Christine with a chagrined expression. He tapped his watch meaningfully with his finger. After a while he went away again.(58)

This conversation takes place as Christine rather frantically prepares dinner for eight people—hosting the apotheosis of an entire novel is no mean feat. The narration repeatedly spotlights the balancing act she plays not only with time (pointed out by her aggressively unhelpful husband Joe) but with physical features such as holding the phone under her chin and opening bags of salad (not to mention availing herself of the wine which will soon play so amusing a role in Benedict’s elfish transfiguration). Of course this comes as Viv waxes resentful on her own marriage with Christine’s father, and the similar demands society placed on her—all the while chastising Christine for cooking chicken over fish and how easy she has it in the modern world. The passage thus confirms de Beauvoir’s distinction between women being born and made,(59) while emphasizing the role the mother plays in perpetuating the cycle.(60)

The parallels in scenic activity and conversation are intricate and complete throughout the entire passage, which spans several pages to open the final chapter.(61) Here we have the narration focusing its attentions not (as much) on the idiolectal level, within the domain of Stylistics—although the uneven, halting nature of the long second sentence in the quote above does nicely evoke Christine’s frenzied multitasking—but on the slightly broader syntactical one, the world of Narratology, stitching together a scene in such a way to effect an understanding of character and narrative situation. ‘The mother does not greet a daughter as a member of the chosen caste: she seeks a double in her. She projects onto her all the ambiguity of her relationship with her self; and when the alterity of this alter ego affirms itself, she feels betrayed,’ de Beauvoir writes in The Second Sex.(62) In Christine’s relationship with her mother, this genesis of conflict continues to resonate after four decades.

The mother as the definitional epicenter of de Beauvoir’s ontological ambiguity of women; this is the examination Arlington Park performs with its varying narrative techniques that allow it to approach the socio-cultural-maternal relationship from either temporal end. But what of the mother herself? Two hundred pages before her phone call, Christine ignites an introspective Juliet to comprehend her own death.

She had met Christine Lanham on her way back from the supermarket. Juliet was carrying her shopping in plastic bags. She had Katherine and Barnaby with her, and she was carrying her shopping because Benedict took the car to work. How are you, Christine said, amazed. She hadn’t known Juliet had lived in Arlington Park. Has she just arrived? Juliet said she’d been here for nearly four years and Christine was amazed again. In fact, she was more than amazed, Juliet saw: she was disappointed…

How are you, Christine said, and Juliet nearly replied, Actually I’m dead. I was murdered a few years ago, nearly four years ago to be exact.(63)

The moment is the initial crash of Juliet’s past into her present, in something like an inversion of the technique employed to disseminate Solly’s maintenant.(64) Taking place (via memory) as Juliet gets ready and avoids Benedict touching her, the immediacy of that past—and the (now unrealized) exceptionalism it represents—is reflected in the narrative mode, an early precursor to the Outline trilogy’s first-person free-indirect, the collapse of all narrative intermediaries between Christine’s questioning presence and the scenic present.(65)

A page or so on and we learn the truth about Juliet’s life.

What she’d actually said to Christine Lanham was: We came here for my husband’s job. She’d explained it to her, every detail. She’d said, My husband likes to move around every few years, you see. He’s a teacher, she said. He specialises in failing schools. He sounds fascinating, Christine had said, so that a bitter feeling of pride had risen into Juliet’s mouth…She’d acted as if it was no concern of hers what she did. So I usually just find work locally, she’d said.(66)

Actually I’m dead Juliet imagines herself saying, meeting an old pseudofriend on the street. The fact that we don’t get her actual reply to Christine for another page of Juliet’s fictive present negotiation of Benedict and the children foregrounds the response she wishes she had given over the one she gave. Juliet lives in an ongoing void of meaning, a stateless existence that causes her to move around the country at the whims of her husband’s important, fulfilling job, leaving her to ‘find work locally’—even if it results in her running at a dead sprint across the town from which she had once hoped to escape in order to not be the absolute last mother to retrieve her children from school.

And those children need to be got out the door as Juliet moves through her morning. Immediately after tumbling Barnaby off his delinquent mountain of bedclothes, she arrives in the kitchen, where a whimsical Benedict is playing a recording of Melanie Barth singing in French.

The sound of it brought tears to Juliet’s eyes. It was the voice, that woman’s voice, so solitary and powerful, so—transcendent. It made Juliet think she could transcend it all, this little house with its stained carpets, its shopping, its flawed people, transcend the grey, rain-sodden distances of Arlington Park; transcend, even, her own body, where bitterness lay like lead in the veins…

“Her French is just exquisite, don’t you think?” Benedict said to her.

He was reading the sleeve notes, where a photograph showed Melanie Barth standing in a green ball-gown on a beach, gazing out to sea. Juliet wanted to tear it from his hands, tear it and destroy it, rip Melanie with her exquisite French to shreds. Of course her French was exquisite! She hadn’t had to spend her life looking after Benedict, buying food for him, washing his clothes, bearing and caring for his children! Instead, she had thought about herself: she had brushed up her French and then she had gone down to the beach in her ball-gown.

Juliet did not feel transcendent any longer. She felt angry, dense and angry and dark, compacted, like lead.(67)

Another precise example of dexterity in point-of-view, the free-indirect style capturing the immediacy of Juliet’s emotion and thought and the psychonarration pulling back slightly to wash over her ultimate resignation. The moment also is a textbook unification of narrative and textual functions. What could be more emblematic of Juliet’s disillusionment than her shoemaker husband blissfully playing a record as he packs his things to go to his fulfilling job? The narrative repetition, playing on that existentially-loaded term transcendence, relates the absurdity Juliet feels, the disconnect between her desire for purpose and the bare facts of her life. To whatever degree the word is used, as it were, intentionally, there is a clear confrontation between Juliet’s being-in-situation and self-defined sense of self, in a perhaps more de Beauvoirian than Sartrian manner. Juliet sees in her life a harsh boundary on her possibility—her transcendence is a mere illusion. She faces an endless cycle of days that will see her ultimately impose the same life onto Katherine; a condemnation to condemn. She rages, to herself; she does not like Solly go quietly into that eternal day. But she is ultimately faced with a grey, damp present all the more damning for its pernicious stability; opposed by motherhood that traps her sense of self internally, that represents a death of freedom which cannot be said.

Declension d’Elle-Même: Amorality and the Conflagration of the Female Narrative

She wanted to explain it to him, but she couldn’t be bothered. She was too drunk.

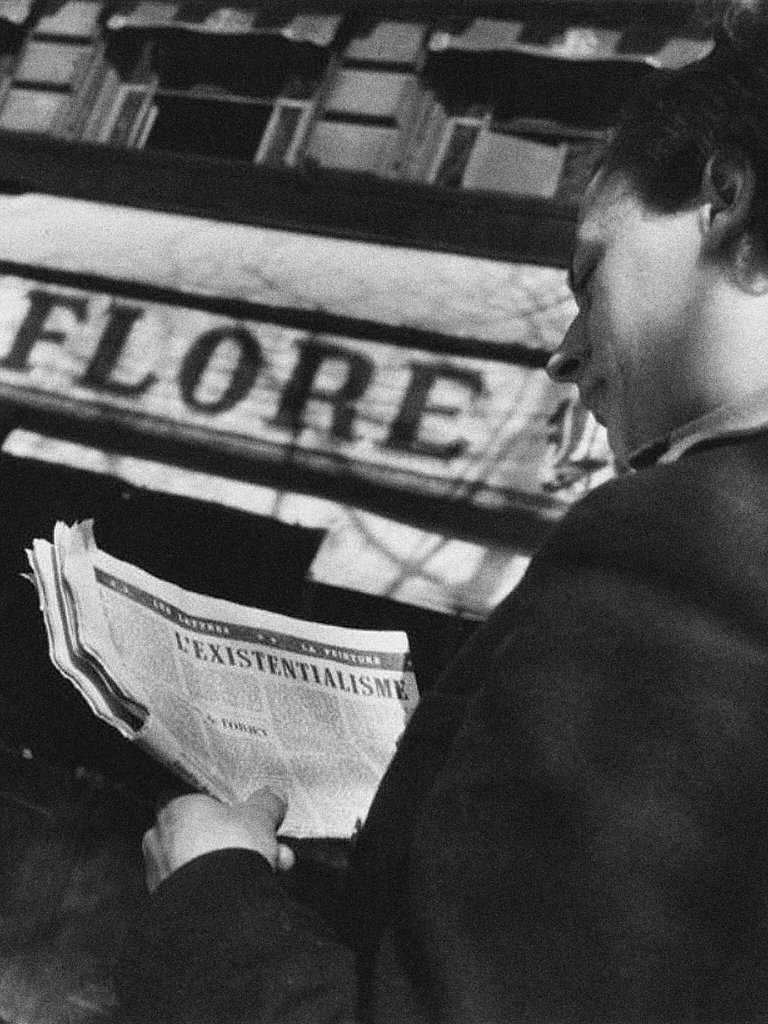

Ce qu’il y a de commun entre l’art et la morale, c’est que, dans les deux cas, nous avons création et invention.

–Jean-Paul Sartre, L’Existentialisme est un humanise

And it is in shadow of this death that Arlington Park makes its most profound statement. A statement, indeed, about nothing. We have seen the methods the novel uses through to capture the lives of the women as they are bound by the daily. Perhaps its most powerful statement is articulated with silence: the lack of moral or ethical judgment about the characters made by the narration. This maneuver, which we might call narrative amorality, is achieved both extra- and intra-textually and defines Arlington Park a novel of afeminist feminism, one that obviates the traditional female narrative as found in contemporary fiction.

In his lecture-comme-essay L’Existentialisme est un humanise, Sartre responded to the accusations of nihilism leveled against his philosophical system by reading into his prior work a mandate to securing the freedom of others; essentially, that to act ‘wrongly’ is not to violate a universal moral code (which he must and does maintain to be nonexistent) but to be ‘inauthentic’. This somewhat dubious addendum to his existentialist philosophy is perhaps aimed more at pragmatic attempts to appease critics from a postwar public and the French Communist Party than anything,(68) but nonetheless has become a central tenant of existentialism that all major thinkers in the tradition uphold. Our overriding goal—to dissect narration as it encounters existentialism, and not to impose the latter onto the former(69)—is therefore especially apt, for there is no morality, no ethical imperative to be found in Arlington Park.

‘And this is where the paradox of their [women’s] situation comes in: they belong both to the male world into a sphere in which this world is challenged; enclosed in the sphere, involved in the male world, they cannot peacefully establish themselves anywhere,’ says de Beauvoir in something of a maxim for much contemporary literature.(70) Arlington Park is, on the most fundamental level, an emphatically feminist work, in that it seeks to portray through narrative women’s lives, situations, and complications. In a classically Cuskian manner, however, it refuses to either to reject the traditional female narrative or to reinterpret it, therefore precluding the difficulties arisen by the contemporary marketplace’s demand for a certain mode of engagement by ‘female’ novels, a requirement of morality.(71) The current feminist narrative must either reject this traditional (fe)male novel through characters that struggle with oppression (wherein the book makes a moral statement about the ills of patriarchy and gender expectations) or reinterpret it with characters who triumph as independent beings—the ‘unlikeable female protagonist’ paradox—but who thereby orbit around an absence of that traditional (fe)male narrative, therein making a/that same moral claim about the world and socio-gender status. One cannot reject that which does not exist. This requirement of morality thus locks contemporary fiction on a continuum of gender relations, limiting the (traditionally understood) feminist novel to, in practice, one of two extremes. Rachel Cusk has obliterated this binary her entire career. Her novels (and especially her memoirs, as has been heavy criticized) are all amoral, Outline perhaps the most obviously. But Arlington Park is equally as complete a work of narrative amorality, and as such offers an indelible feminist critique of feminism.