KK Fiorrucci

Short Fiction

A certain man, in a certain town, in a certain land, having been fashioned, on a certain day of a certain month of a certain year, a certain number of years earlier, by a certain man, which is to say, a similar but different man, and, it cannot be denied, a certain woman, according to certain processes, natural processes, little-discussed but well-understood (with a certain pleasure taken on either side and certain feelings, again on either side, arising upon announcement of the happy news) and born, after a certain period, in a certain room of a certain building at a certain time in a certain season of a certain year, a room with its own door and number, a certain distance from the main door, that is, the door of the building, which had its own number, different from the door of the room, the same room through which a certain man now passed, who was neither the man himself nor the man who had fashioned him with the woman, but a third man, then engaged in a series of mental observations directly pertaining to the man’s birth and intending to repeat them, more or less, in writing immediately thereafter, found himself, which is to say the man then being born in the room, not the man passing through the door of the room, who was dead or long-dead by this time and hardly in a position to make observations on another man’s birth, on that day, in a certain room of a certain house of a certain town in a certain land, while certain birds sashayed along certain power lines, a certain position and brilliance was attained by the sun, and certain power lines trembled beneath certain full-of-themselves birds, he, the man, found himself in a certain mood, a mood one could hardly deny had been produced by the combination of certain events, in the days and weeks immediately preceding that day, with certain other events, taking place from the period that lasted in the days and weeks immediately following the day of his birth until the days and weeks immediately preceding that day, which is to say, the present day, some of which were talked about but little-understood, while the rest, but not all the rest, were understood in silence, near-silence. It was a mood of certainty.

Near-certainty! Well, fancy. As he sat there, thinking all this and thinking very little, noting then certain shapes left by, or in, the snow, either melting or presently unmelted, and transposing his mental notes into written remarks that might be read and understood by anybody; as he sat there, watching water course down the hill, was it water, he slid, as he sat there, headfirst, into a dream, partly or fully, headfirst or feetfirst, the particulars of which are lost and, in any case, irrelevant for these purposes. He was a certain man, that is all, and wished to go on a journey, which is not in itself unique.

After the moment of certainty, near-certainty, and the dream, he awoke. Heard himself breathe. The world introduced itself very crisply. Talked, breezily. It was the moment of certainty. True near-certainty.

Certain events would occur, in the days and weeks immediately following that day, which is to say, the present day, but not the present moment, which is to say, today; most of them would fail to involve him, though a few would affect him in ways he had been told about but did not fully understand. Almost everybody else who ever lived would turn out never to have heard of him, and the few who did – without exception contemporaries or near-contemporaries in time – would think of him but rarely and even then, briefly, partially, inaccurately. When these events were concluded, the man would die, and certain arrangements would be made, either deriving from certain wishes he had previously formed in his mind and dictated to a certain other person, wishes that would be buried and exhumed at the relevant moment, that is, the moment of death, or in the absence of such wishes, according to certain conventions generally established for the swift disposal of a body in the absence of unambiguous personal wishes, usually fire or burial, and while the arrangements were being made to enact the wishes or absence of wishes, the man’s body would conclude certain processes not requiring the presence of unambiguous personal wishes by its owner, or former owner, and a short time after this, the flesh would degrade and the body come apart, more or less quickly depending on the pre-agreed method of disposal, with the man being, for a short time, on the lips of those few others who had known him while he was still a man, distinct again, a moment of understanding that would, though providing little comfort to the man at that time, succeed him. All this renewed interest in the man would culminate in the gathering of a certain number of those who had encountered him while he still inhabited the body they were burning or burying that day. Certain others would attend too, who had never met him, but had been employed to carry out certain tasks, including the conveyance of his body from certain buildings and facilities to certain others, the delivery of a short speech noting certain events judged, through prior consultation with the man’s encounterees, to be the most important in the man’s life, all the while drawing attention to the better points of his character and largely disregarding the flaws, unless these had been so flagrant or numerous that it might be disrespectful in some way to avoid mentioning them (which in the man’s case they were not), the utterance of certain words and phrases it was customary to employ whenever a certain person died, not specific to the man, and, finally, the introduction of speeches from certain others who had known the man, which elaborated on the initial description of the man’s life that had been given; some would take the form of vignettes while others would be general impressions, largely disconnected from chronology and aiming to paint a more or less complete picture of the man as he had lived, the things he had liked and disliked, believed, said he believed, and said, and all of these would be gratefully received by the others assembled, depending on the length of the speech in question, what proportion of the ceremony had already elapsed, and whether they had encountered the man in life, or were simply accompanying someone who had. After the speeches, some of those assembled would make their excuses and depart, while others would travel to another building in order to compare their impressions of the day and its various speeches; in addition, they would exchange their own recollections of the man who had just been burnt or buried and a high point would be reached in the understanding of this man, his character, his way of thinking, and his life, so that, if any one of them had been asked later that evening to sketch him out in a few words, they would each say the same thing, more or less, with some individual variation, to be expected, since portraits are, in the main, self-portraits. They, the attendees, would have taught each other that day how to read him, the man, and he would have taught them something; that they were travellers too, that they had a land to which they would return, like him, eventually, with a day of their own like this, a collective portrait that turned out to be more or less finished, to be hung in each of their homes and considered from time to time. They would continue to think and talk about the man, in the days that followed, and direct their new power, the power of noticing, on all manner of other things, but chiefly on themselves; alas, this and the man’s fame would turn out to be short-lived, and after a certain period of time, there would be very little talk about him at all, near-silence in fact, and after that, there would only be one more day worth noting, and this was the last day he was ever spoken of; after this, nothing much would change, there would be no grand silence – the world would talk, breezily, as it always had, but never again of him. And the understanding of all this put the man in a certain mood, the details of which are hardly relevant, in any case, for these purposes. ‘Story of my life’, he began to say, ‘story of my life’.

KK Fiorrucci is a writer from England. His work has recently appeared in Litro (US), Strix, and Pigeon Review.

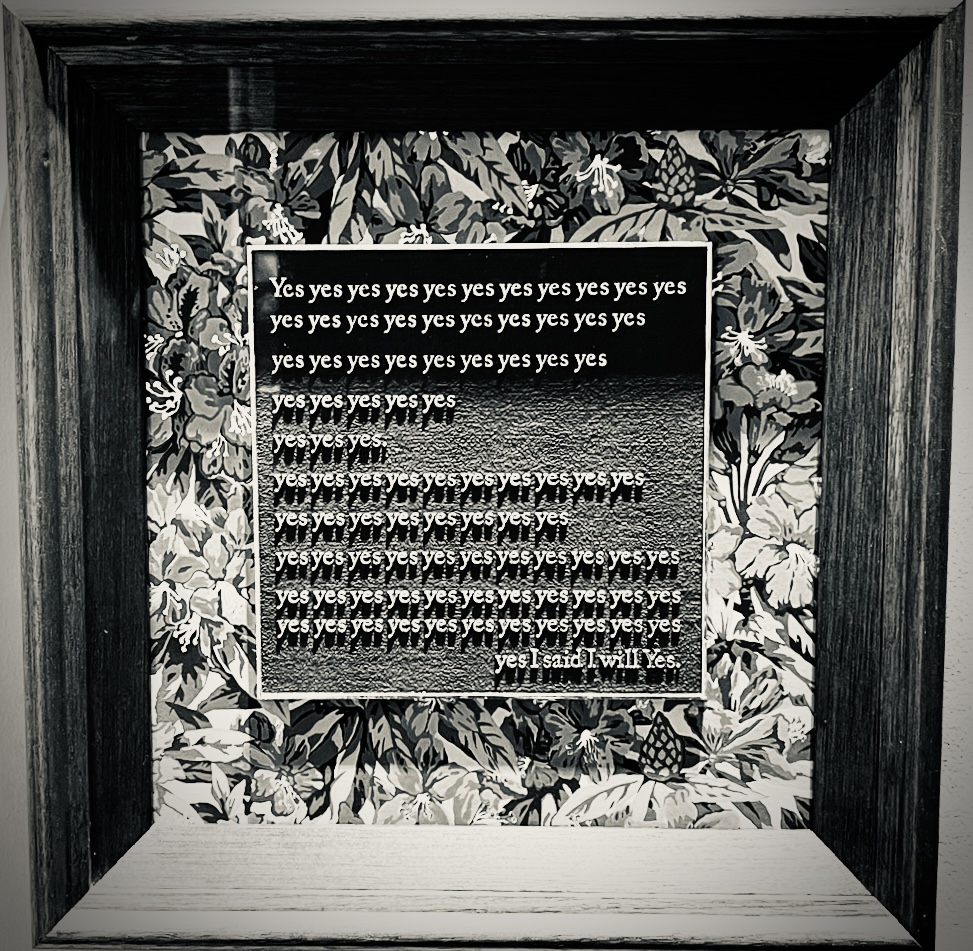

Photo Credit: D. W. White, private collection.