Art as Philosophy

D. W. White

Editorial Meditation

A picture held us captive. And we couldn’t get outside it, for it lay in our language, and language seemed only to repeat it to us inexorably.

Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations, §115

The first thing I thought of walking into my Paris hotel room was that the photograph above the bed conveyed an essential teleological impulse that the photo by the door did not. Teleological is one of those odd words that are extremely, even officiously, common in certain circles, and effectively unknown elsewhere. Squarely within the former circle lays the UIC English Department, for reasons that principally involve an ongoing, inexhaustible obsession with a certain Prussian rabblerouser. Despite my best efforts, a few things have suffused my vocab.1 Dialectics aside, the pictures struck me. They were both of the Louvre.2 The first one, on the wall over the twin beds pressed together in the European fashion, foregrounded the pyramid, with its glass and angles and insistent modernity, placing a portion of palace wall alongside side, on something of equal footing. The other photo, near the door, I only noticed on turning around. Its composition instead relegating a sliver of pyramid to the extreme corner of the frame, spotlighting the ornate Cour Napoleon façade in all its splendor. The photos on each door of the Louvre Floor presented similarly engrossing claims about a possible linear progression of history; my voyages to the elevator were beset by the philosophical potential of radically extant hotel artwork.

There seemed to be a statement made by these photographs, something about the progress of history, or the creep of technology, or the outward manifestations of time. Did placing the more conservative photo by the door signal some subtle condemnation made by the proprietor of touristic greed? Was the picture over the bed indicative of the interior designer gesturing towards an idyllic harmony of tradition and innovation aimed to encourage restful sleep? I was perplexed, and intrigued. So I did what any grad student might do; I wrote down one sentence of notes and went out into Paris, promptly forgetting about my nascent essay idea until the last hours of my trip.3

Which is not to say that teleological impulses did not find their way into my vacation. On this trip I attended Rachel Cusk’s conversation about her new novel, Parade. Anyone who has made it through the first three paragraphs of this essay probably is familiar with and has endured my, shall we say frequent, writings on Cusk’s work. (Indeed I reviewed Parade twice). As part of my involvements with the prenominate UIC English Department, I am doing a PhD prelim list on her novels, as well as teaching undergraduate classes on her books. I’m also at work on a critical book covering her use of narration, some of which has appeared here in L’Esprit. Thus, when I saw that one of the events she was having for the launch of Parade would overlap with my trip, I was treated to that type of nervous excitement which, say, causes one to forget their glasses en route to the event in question.4

Before I left I read Cusk’s Quarry, a small book she released last year as part of The Cahiers Series, published by Sylph Editions London and the American University of Paris. These books are extremely cool. Accompanying her essay which constitutes the text are paintings by Siemon Scamell-Katz, a visual artist who happens to be Cusk’s husband, swallowing up entire pages in moody and expressive swirls of color. Both artists respond to a period living in Greece, which gives Cusk play to zero in on favorite later-period themes of identity, transition, language, and art. “I was beginning a journey into a more savage loneliness” she says, of a time in which their household was beset by illness:

Truth could not stand up to the ugly vigour of facts. A tormenting lack of precision came to beset me in the medium of language. Everything I tried to express was either a kind of cousin of the truth — kindred but different — or else in the act of expression became untrue. The result was that over time the force of memory rose up, no longer held back and contained by the structures of language: it rose up out of the forms I had given it over the years and burst over me in wild, incoherent floods. Unable to make sense of this calamity, it seemed, I could make sense of nothing at all.

There’s a mass laying at the center of these thoughts that provides a glimpse into the concepts Cusk has been orbiting with her more recent work. Beginning with Outline, her career has moved, gradually but surely, into an uncertainty, perhaps even an outright skepticism, of the abilities of language to say anything meaningful about the most significant lived experiences. This, for a writer, begets complication. In the trilogy it was silence given purchase to express a certain trammeled sort of agency; of late it seems even this will not quite do. In Second Place, the direct address worked to amplify Outline’s silence into something with greater instability and increased urgency. In Quarry, as perhaps a nonfiction fugue presaging a more forceful concerto, this distrust of language, earned it seems by a career in living amongst it, sounds its first note, one that rings out with full force in Parade.

What struck me in reading and reviewing Parade was a philosophical acuity and concern of an order not found in fiction, certainly not the contemporary novel. I’ll let my coverage of the book itself stand where it is;5 what interests me here are the hints we find of it in Quarry, and what that might have to say about narrative, history, and linguistic meaning. The quote above gestures towards a certain tension that runs through Cusk’s work, especially more recently: on the one hand an impulse, indeed fundamental need, to communicate in language; on the other, a forceful assertion that truth, at least of those aspects of life closest to the heart of humanity, cannot be accessed through language. It’s a bit like the Sirens, perhaps, working as a drug. The desire to express crashes into and recoils from the awareness that such expression is impossible. Implicit in each is the preclusion of the other. So what are we left with?

To assuage my slight at being denied lodging on the elite Fourth Floor, I took an o’er-hasty trip to the Musée d’Orsay. There I saw the original cast for La Porte de l’Enfer, alongside a rather contemplative fellow who figures prominently in a certain not-unreputable literary magazine’s aspect.6 The trick with museums like the Orsay, however, is to not try and see everything; there’s far too much.7 In a small place—and I mean small like a house, e.g. the Musée Delacroix—you can maybe take a decent look at everything. But it’s senseless for collection on the scale of the Orsay; better to find one or two pieces and zero in. (They offer portable stools for the sitting and viewing of art that you can borrow, for free, in the basement). On this trip I found two, besides my Rodin friends, that seemed to say something about art and its ability to do philosophical work, which, I think, is the point of this essay.

Félix Vallotton’s Femme se coiffant is placed in a row of similarly modest-sized paintings in Gallery 71, Les Nabis. This is upstairs. Despite the direction this essay is beginning to take, I am not a visual art critic. However, Femme se coiffant is the best of the paintings in Gallery 71 of the Musée d’Orsay. The positioning in the scene of la femme, while she coiffants, makes immediately all sorts of profound and compelling claims about gendered expectations of the domestic space, the banalities of the quotidian, the power of observation. Is there “progress” being asserted here, or is it instead a type of soft static acquiescence, promising to forever repeat? The centrality of the clock on the mantelpiece, in harmony with the long, sepulcherian shadows that resonant more as late-afternoon than early-morning, exerts a temporal weight, focusing the viewer’s attention on the inexorable dying down of a day. You can just about hear that clock tick, vying for ocular space with the soft rustle of hair and clothes. Does the modest disorder of the room, coupled with the minutia of the woman’s toilette, say something about interior vs exterior selves, and the routine deception that makes up everyday, outward facing life? I think so.

It’s also just a nice painting to look at, a comment which perhaps underscores the above proviso re: Not Being A Fine Art Critic, but is true nonetheless. I suppose I could fashion something about the approachability of the pastels, and the overall warmth of composition, as grounding the ontology of Femme se coiffant in its artistic makeup, via a unification of the domesticity of the rendered scene with the accessibility of the technique to so render; while pointing out how any mimetic avenues towards verisimilitude seem to be at best backgrounded and at worse outright neglected, given the dubious physics of the side table (bonnet holder?) and the bed’s collision with the wall; but I think I’ve made my point.

Compared to Femme se coiffant, Édouard Detaille’s Le Rêve is much bigger. It is across the hall from Gallery 71, which in the Musée d’Orsay means a sprawling atrium of humanoids, in both marble and flesh, prowling around the place the trains used to run.

Le Rêve is, sensibly, a painting of people dreaming, specifically soldiers, more specially about other soldiers. It is an arresting picture. As I mentioned, it is very large. This both imposes on the viewer a productive sense of scale while being something of a hinderance to the appreciation of the fine details and generally making out the scene in and of itself.8

There is quite a bit of teleological-type stuff happening here. The Napoleonic soldiers who are being dreamt are quite literally marching right-to-left towards glory and history, for one. The line of troops doing the dreaming, and especially their neatly stacked rifles, run off in vanishing perspective towards progress. Then we have the relative serenity of the “fictive present,”9 which implies a carved-out space for reflection and reminiscence, even and especially while asleep. Even the dog has his guard down. The point here is the remembrance; the soldiers are significant not for the military prowess—in which they in no way seem engaged—but their link to history, their awareness of the past, of their own lineage and ancestry, of the evolution—in arms, knowledge, and tranquility—they represent when compared with their forerunners, whom they nonetheless admire and respect. There is literally a light at the end of the tunnel.

Le Rêve was first displayed in 1888, and was apparently quite successful. I can see why. It’s a really cool painting. The overt themes of patriotism and military strength, with the sting of Franco-Prussian war not yet faded, couldn’t have hurt public response. Of course, the fact that within thirty years France, and all of Europe, would be dragged through the cauldron of the most infernal war the world has known, seems to complicate the whole linear-march-of-history thing. And that’s often the trouble with teleologic view: the future.

But back to our language-as-sirens notion. The Quarry Paradox, maybe we’ll call it. I keep finding this idea, all around me. It’s an old idea, though; in fact I think the most interesting connection is in Wittgenstein, and his impossibility of private language. The confluence of these ideas is clearly going to have to be an essay unto itself; I’ve made peace with that. This essay, then, is maybe a bit of a warmup.10 Part of the broad architecture of argument I’ve been building for the PhD involves defining Modernism (at least in literature) in way that runs clear through to Cusk’s work. Among the things we find in the (High) Modernist novel is play with style and syntax such that words are given priority over language. Molly Bloom’s monologic close to Ulysses is perhaps the best example of this technique. It seems clear that there is some sort of meaning achieved by the text beyond, outside, and even despite its grammatical denotation (or lack thereof). What might we say, for lack of a better word, about such a maneuver, philosophically speaking?

Interior life—that is, consciousness—is, in the psychologically-focused, character-driven novel such as has effectively defined “literary fiction” since Jane Austen, the driving central force. Among Modernism’s great achievements is to find new methods towards verisimilar renderings of interiority among its characters: the famous “stream-of-consciousness” techniques. (Plural). Following Wittgenstein’s impossibility of private language, however, we might see this interiority as mimetically inaccessible via even the most sophisticated heterodiegetic narration; there is always something beyond language that pulses at the core of consciousness. Therefore, in response, Modernist literature re-orients itself such that language (as words) achieves ontological significance via aesthetic, not mimetic, meaning. There can be no true “transcription” of inner life, not quite, and so the artistry of the literary form, grounded in words qua artistically relevant entities, approaches this sought-for truth of lived experience via the aesthetic immediacy available to visual arts. Couple this with Wittgenstein’s dream of philosophy as poetry, an art form unto itself—it is the doing, even the getting it wrong, that counts—and we begin to see the powerful interpretive possibilities open up by such a pairing. Truth is not found in the thing pointed to but in the gesture of pointing itself:

All explanation must disappear, and description alone must take its place. And this description gets its light — that is to say, its purpose — from the philosophical problems. These are, of course, not empirical problems; but they are solved through an insight into the working of our language, and that in such a way that these workings are recognized — despite an urge to misunderstand them. The problems are solved, not by coming up with new discoveries, but by assembling what we have long been familiar with. Philosophy is a struggle against the bewitchment of our understanding by the resources of our language.11

Assembling—and, we might add, reassembling—that which we have been long familiar is a project laying at the very center of the Modernist project, alchemizing the quotidian such that it moves towards the sublime. Cusk, in her own way, is not the successors so much as the continuance of this tradition, complete with the overwhelming urge felt by the marketplace to misunderstand her.

I stayed in Paris through Bloomsday, naturally. The security guard at Shakespeare and Company, who had been very helpful in discerning my episodic French a few days prior during the Cusk event, kept watching the admittedly excellent festivities. The readings, the music, the cheese. Fresh groups of people, in ones and twos and threes, kept coming onstage to read the opening of all eighteen of Ulysses’ episodes. And maybe that’s what Modernist literature compels, an artistic immediacy born of the complete trust placed in the reader via that quintessential refusal of the easy and the expected. You can’t look away from a Modernist picture, if you’re going to engage with it at all. And you can’t help but listen to the preeminent Modernist novel being read, even if you’re at work, shepherding hordes of rainsoaked tourists standing in outstretched lines of disintegrating integrity, waiting to get inside and take pictures of themselves buying books.

That Modernist dismantling of convention, and insouciant orientation towards rules such as linearity and grammar, invites just the type of re-calibration towards ontological coherence demanded of by our Wittgensteinian skepticism of meaningful linguistic expression. Quarry specifically is a fascinating example; the inclusion of visual art, a medium that of course bypasses language and as such is often the thing which, through its extralinguistic communicability, can be used to demonstrate the viability of thought as antecedent to verbal expression.12

Cusk’s navigation of this tension, a major theme in her last few books, represents a new frontier in her oeuvre. Everything in the kaleidoscopic composition of the novels—the innovation in movement between narration sites, the panopticonic investigations of self, the poetic richness of the prose—works towards rendering them as ontologically meaningful works of art. Added to this, her method, unlike Woolf and Joyce with their elision of grammar and stylistic pyrotechnics, has increasingly been one of direct contemplation. The philosophical inclination of her work has increased instep with its perspicuity; Cusk’s novelistic narrators—and in The Last Supper or Quarry, her essayistic self—possess a mind-style of potent intellectual rigor and depth:

There is usually an artist somewhere at the bottom of that story of spoliation. A long time ago, by virtue of their aesthetic instincts, artists found the beautiful places and they came to them with other artists and feasted on their beauty and their flavoursome reality, and then they set about creating with their brushes and their pens the first copies. They made copies not only of what they saw but of what they were and what they felt, of their physical and sensory pleasures, their freedom and their entitlement and their sensuality. Once that discovery had been made, that the world and its experiences could be reproduced, each of us came to expect that for a certain sum we could have a copy of our own. But every time a copy was made, it seemed that its distance from the original had become greater.

If there’s progress here it is the Devil’s progress; an illusion foisted upon the unwitting, Promethean mankind by Descartes’ demon; creation, as with Saturn, as destruction. There’s a lurking sadness to these passages, a melancholic aspect that seems at once to have reconciled but never fully accepted the limitations of the medium to which its creator has devoted her artistic life and career. It’s a sadness which is not admitted in the crusading, teleological view of history, be it Marxist literary theorists, earnest societal commentators, or pious Christian thinkers13; it is thus often not admitted in the current literary marketplace, if divorced from right-minded morality arcs. But Cusk has long obviated such concerns; probably the most admirable thing about her work (certainly, for my money) has been her conviction in literature as sufficient unto itself, and its attendant necessity. Art, for Cusk, is no piacular act.

On the hottest day of my unseasonably cool trip I trekked across the Tuileries dust to the Musée de l’Orangerie. There was scaffolding all over the park, readying itself for Olympian tourism. I went in to see Les Nymphéas, Monet’s serene still-lifes that radiate out in a series of antechambers stacked on end, and which make about as compelling a claim against the onslaught of human industry as one could hope to find. There is no room for the eye of the observer in the water-lilies, not to mention his camera. But on the ground floor I found another account, one that achieved a similar end while carving out a bit more space for a witness.

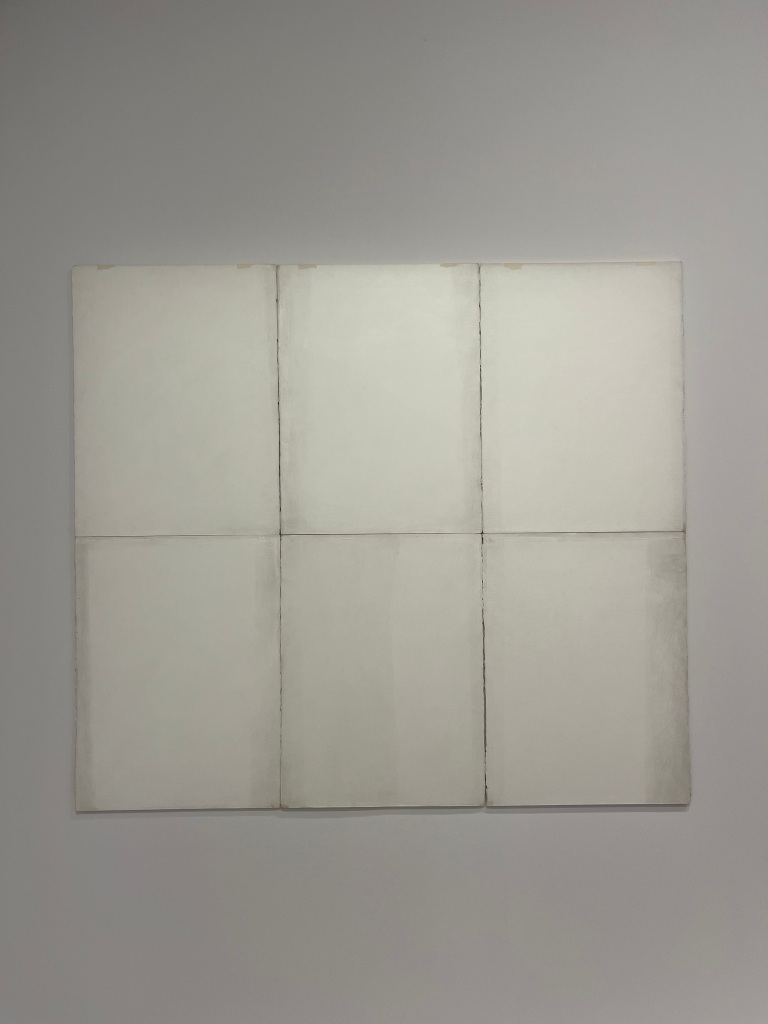

On temporary exhibition was Robert Ryman’s series of white paintings, mostly large squares and other rectangles that were, well, white. As noted in the museum guide, this exhibit centered the “Act of Looking,” featuring pieces that Ryman described as being “devoid of illusion or symbolism.” The major theme here was mutual observation, the type of symbiotic relation that I thought might help me out in my quest to understand what it was that art was saying about progress. “As such,” the exhibit implored, “we too must begin to look at Ryman’s painting as the artist encourages us to: as active painting, painting that invokes as much the painter’s gaze at that of those for whom it is destined (the visitor, or rather the viewer).” I gave it a shot.

There seemed to me a compelling response to the teleological to be found in these white paintings.14 Much like Michael Fried says of Modernist painting’s ability to defeat theatricality by facingness—the trend of painting “for the viewer” overcome by a technique wherein the viewer is accounted for but disregarded—Ryman’s hyper-regard seems to offer a method of defeating the demand for utility in art; a demand that has seen a troubling renaissance in our current age of vapidity and ever-increasing speed; a demand that risks vitiating art into entertainment. The Marxists have gotten at least one thing right: commercialism, in art no less than anywhere else, is like a drug: the more you give the more it demands. Much like Modernist literature, this defiance of the beholder weaponizes the expository elements endemic to all dialogic forms of communication—which includes even the most post of the postmodern—into internally coherent artistic architecture, moving away from didacticism and towards aestheticism. It is of course another way of grounding an ontology in the composition rather than the statement, subsuming the philosophical claim within the art’s inner workings, thereby deepening the whole. Ryman seemed to have understood this, in his minimal way. Among current novelists, very few approach Cusk in this skill.15

Later in Quarry, one begins to sense something that has stood out to me in the interviews I’ve listened to, including the one I went to on my trip: her unease with any sort of grand pronouncement, especially anything actually said in language. As a writer with an extensive canon of work, Cusk is often asked questions about the scope of her career. After all, surely she has been building towards something, surely there is a clarity now achieved in which everything might be seen in brighter light:

Parts of the quarryman’s narrative were lost to the roar of the engine and to the drama of the road with its sheer drop, which the truck seemed at risk of plunging into the more distracted he became by his story. I was frightened, almost angry: I wanted to get out of his truck, his story. Gratified by the presence of an audience, his finger carelessly on the steering wheel as we veered again and again toward the edge in the gathering dark, he seemed to represent a force that prejudiced one reality against another, that rendered my own reality lesser, unreal for the reason that it was not bonded in the same way to what bore the name of progress. My own history appeared to me as one in which I had been continually morally isolated in the midst of actions and decisions that had the highest individual significance while commanding the lowest public and actual value. If I hadn’t taken the trouble throughout to write things down with the greatest exactitude of which I was capable, this history would have gone unrecorded.

Or perhaps, amidst her evergreen descriptive powers of physical place, any sense of narrative, any cogent formulations of history, are one chaotic quarryman’s slip of the wheel from tumbling into the abyss. Perhaps narrative as force of coherence is one that necessarily deludes personal agency. It’s possible that the photos in the hotel are easy to look at and sensible for rooms on the Louvre Floor; it’s possible forgotten glasses are less psychosomatic manifestation and more random chance. Maybe we follow ideas like sirens across dangerous terrain and Parisian streets alike, simply because it is what we do. The gesture makes the meaning of the act. Perhaps we use language simply because we haven’t yet found anything else, and write because we must. Whose teleology? After all, manic compulsion can look quite a bit like divine ordainment, at least for a little while.

*

Endnotes

- Thankfully nothing phallic, the Omega to UIC’s Marxist Alpha. ↩︎

- Indeed my floor, the fifth, was the Louvre Floor. I rather was hoping for the Musee d’Orsay, with its excellent clock and entrance to Hell, or maybe the stately Arc de Triomphe, but at least I didn’t get stuck on the third floor, given over to “the bridges of Paris,” which seemed like something of a slight. ↩︎

- This also accounts for the falsity of the photos in this section. The ones of the works in the room are, I am sorry to report, indeed not the photographs I encountered in my hotel room. I naturally only remembered to take pictures of the pictures after I’d checked out. The rest are legit. Thus the pieces in this photojournalistic travesty are an amalgamation of crude approximations sourced from Google, as well a surreptitious, post-checkout trip to the fifth floor to snap a few clandestine shots of various doorways and salvage some integrity for this portion of the essay. ↩︎

- Arriving preposterously early, coupled with my near-Costanzian squinting abilities, meant that I could still see well enough. ↩︎

- Which was here and here, for anyone who may have missed the earlier links. ↩︎

- The Musée d’Orsay is the best place to see The Gates of Hell, of the iterations I’ve come across at any rate. The lighting in there is pretty incredible. Le Penseur, however, is much better observed in its original form at the nearby Musée Rodin, although on this trip he was under scaffolded restoration, which felt like a bit of a ill omen vis-à-vis the fortunes of this particular literary concern. ↩︎

- Don’t get me started on the Louvre. ↩︎

- I neglected to take any pictures of the zoomed out gallery for this one, unfortunately. Again, not a photojournalist. But trust me, it’s really big. ↩︎

- Not sure if that works for painting. ↩︎

- Nobody steal my idea. ↩︎

- Emphasis original. From §109 in my edition of Philosophical Investigations, the Revised 4th Edition from Wiley-Blackwell, translated by Anscombe, Hacker, and Schulte. James Klagge’s recent book, Wittgenstein’s Artillery, is recommended to anyone interested in the poetic potential of philosophy. ↩︎

- I’m also not a linguist, but try explaining a color without mentioning any other colors, and see if that works better than showing someone the color. The same thing works really well for the flavor of bubble gum (although sadly I don’t believe there’re any pithy thought experiments involving Mary in a room with chewing gum). ↩︎

- The notion that all of these groups are fundamentally Christian in worldview—evangelical impulses come to the same thing in the end, whether one ascribes their ultimate source to God or not—would be meet with revulsion by at least two, and come to think of it, probably all three, of them. ↩︎

- I also liked the tagline of the exhibit: “Le blanc a tendence à rendre les choses visibles.” I may or may not have procured from the gift shop a mug with this quote to serve as writing-desk inspiration. ↩︎

- Lucy Ives would certainly be one; Life is Everywhere is a staple of my undergraduate class that’s principally on Cusk. ↩︎

D. W. White writes consciousness-forward fiction and criticism. He serves as Founding Editor of L’Esprit Literary Review, Prose Editor for West Trade Review, and Executive Editor and Director of Prose for Iron Oak Editions. His writing appears in The Florida Review, Another Chicago Magazine, Necessary Fiction, and Chicago Review of Books, among others. He is currently pursuing his Ph.D. in the Program for Writers at the University of Illinois at Chicago, where he teaches classes on Modernism, Rachel Cusk, and the Self.